Promoting Healthy, Meaningful Aging Through Social Involvement: Building an Experience Corps

(Editor’s note: Pathways responsible for higher-order thinking in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), or executive center of the brain, remain vulnerable throughout life—during critical early-life developmental windows, when the PFC fully matures in the early 20s, and finally from declines associated with old age. At all ages, physical activity and PFC-navigated social connections are essential components to maintaining brain health. The Experience Corps, a community-based social-engagement program, partners seniors with local schools to promote purpose-driven involvement. Participating seniors have exhibited immediate short-term gains in brain regions vulnerable to aging, such as the PFC, indicating that people with the most to lose have the most to gain from environmental enrichment.)

Over the last decade, scientists made two key discoveries that reframed our understanding of the adult brain’s potential to benefit from lifelong environmental enrichment. First, they learned that the adult brain remains plastic; it can generate new neurons in response to physical activity and new experiences. Second, they confirmed the importance of social connectedness to late-life cognitive, psychological, and physical health. The integration of these findings with our understanding of individuals’ developmental needs throughout life underscores the importance of the “social brain.” The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is particularly integral to navigating complex social behaviors and hierarchies over the life course.

Over the last decade, scientists made two key discoveries that reframed our understanding of the adult brain’s potential to benefit from lifelong environmental enrichment. First, they learned that the adult brain remains plastic; it can generate new neurons in response to physical activity and new experiences. Second, they confirmed the importance of social connectedness to late-life cognitive, psychological, and physical health. The integration of these findings with our understanding of individuals’ developmental needs throughout life underscores the importance of the “social brain.” The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is particularly integral to navigating complex social behaviors and hierarchies over the life course.

In this article, I will briefly articulate how the above findings inform the design of a social health-promotion program, the Experience Corps, which leverages seniors’ accumulated experiences and social knowledge while promoting continued social, mental, and physical health into the third age, when a person’s life goals are increasingly directed to legacy building. Experience Corps harnesses the time and wisdom of one the world’s largest natural growing resources—aging adults—to promote academic achievement and literacy in our developing natural resources—children—during a critical period in child development. In so doing, older volunteers instill a readiness to learn that may alter the child’s trajectory for educational and occupational attainment, as well as lifelong health. At the same time, preliminary evidence suggests that the senior volunteers experience measurable improvements in their cognitive and brain health.

The Developing Prefrontal Cortex

The prefrontal cortex is the brain’s planning, or executive, center. It integrates past and present information to predict the future and to select the best course of action. Executive processes generally involve the initiation, planning, coordination, and sequencing of actions toward a goal. While we take these skills for granted, the brain requires considerable resources to navigate unpredictable environments and to integrate the multiple streams of information that each of us calculates hundreds of times per day. We often must flexibly and quickly update plans and priorities and inhibit distracting or irrelevant information in the environment and in memory that may direct attention away from a goal.

The PFC is evolutionarily the newest and largest region of the brain, and its growth over the millennia corresponds to the increasing importance of social behavior to human survival. Over time, collaboration and negotiation became at least as important to our survival as agility. PFC maturation is not complete until one’s early 20s,1 presumably because the ability to integrate multiple streams of information requires the maturation of physical, linguistic, and emotional sensory networks.2 The PFC’s extended developmental window involves maturation of networks that control attention steadily from childhood to adulthood, allowing us to filter multiple streams of information more efficiently.3, 4 For evidence, we have only to look at the decisions that adolescents make; teens are often enamored with living in the moment and considering the consequences later. With age and experience, these priorities reverse and thoughts of consequences prevail over the moment.

During the PFC’s developmental window, the brain may be particularly vulnerable to insult.5–8 Early-life brain imaging and cognitive testing studies show that lower socioeconomic status (SES) in children, as measured by family income, is associated with developmental lags in language and executive function and their associated brain structures, like the PFC. We do not yet know if these maturational lags make the brain more vulnerable to the effects of additional insults that accumulate with age, nor do we know how modifiable or reversible these imprints are in a fully developed adult brain.

In addition, we do not yet know whether socioeconomic deprivation in early life leaves a lasting imprint on the developing brain. We have established that birth to age two is a critical period of rapid brain growth and development, and head growth is 75 percent complete by age two.9 From age two to seven, language typically develops rapidly through spoken and then written expression. As such, there are critical windows of brain and language development that, when nurtured among children of all socioeconomic backgrounds, may lead to long-lasting effects on school success, occupational opportunities, and cognitive and psychological health throughout life, thus reducing economically related health disparities.

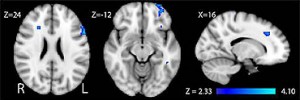

The late-developing PFC appears to be more vulnerable than other brain regions. With increasing age come increasing difficulties in executive control. Through longitudinal observation, we have found that components of executive function decline earlier than memory in older community-dwelling adults, and intervention targeting these components may delay and mitigate memory decline that leads to dementia.10 Consistent with this finding, studies of the aging human brain show that loss of brain volume is greater in the PFC than in posterior areas of the cortex.11–15

Healthy aging is not defined simply as the avoidance and management of chronic diseases. Healthy behaviors, including physical activity, social supports and engagement, and cognitive activity, remain important to overall health and prevention of cognitive decline and disability as people age—even into the oldest ages.16, 17 However, it has proven difficult to motivate older adults to participate in health-behavior change programs, especially for sustained periods of time.18 According to developmental psychologist Erik Erikson, the third act of life represents an opportunity to use a lifetime of accumulated knowledge—the kind of knowledge that is not easily memorized from books, classroom lectures, or online searches—to find purpose.19 This type of knowledge comes from decades of interpreting and understanding unpredictable social behaviors in order to predict and shape future rewards—not one’s own future, but that of succeeding generations through the legacy of transfer. I will outline here a rationale for valuing these abilities and, in so doing, identify a vehicle by which to maintain cognitive, physical, and social activity throughout life to buffer the effects of age and disease on the mind and body.

To continue reading this article by Michelle C. Carlson, Ph.D., published in Cerebrum, please click Here.