Teaching is the art of changing the brain

James Zull is a professor of Biology. He is also Director Emeritus of the University Center for Innovation in Teaching and Education at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio.  These roles most assuredly coalesced in his 2002 book, The Art of Changing the Brain: Enriching the Practice of Teaching by Exploring the Biology of Learning.

These roles most assuredly coalesced in his 2002 book, The Art of Changing the Brain: Enriching the Practice of Teaching by Exploring the Biology of Learning.

This is a book for both teachers and parents (because parents are also teachers!) Written with the earnestness of first-person experience and reflection, and a lifetime of expertise in biology, Zull makes a well-rounded case for his ideas. He offers those ideas for your perusal, providing much supporting evidence, but he doesn’t try to ram them into your psyche. Rather, he practices what he preaches by engaging you with stories, informing you with fact, and encouraging your thinking by the way he posits his ideas.

I have read a number of books that translate current brain research into practice while providing practical suggestions for teachers to implement. This is the first book I have read that provides a biological, and clearly rational, overview of learning and the brain. Zull provokes you into thinking about his ideas, about your own teaching practice, and ultimately, what it means to learn.

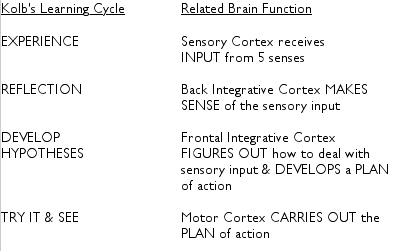

Zull doesn’t lecture here; rather, he discusses his ideas so you can follow their progression. The impetus for his ideas stem from David Kolb’s 1984 book, Experiential Learning. Kolb’s model contains four portions:

- - engaging in a concrete experience

- - following it with reflective observation

- - developing an abstract conceptualization based upon the reflection

- - actively experimenting based upon the abstract

Kolb’s model, like Zull’s, is a cycle, and therefore it is possible to jump in at any point in the process. Zull takes Kolb’s model and provides the biology.

Zull’s conclusion is that:

Zull’s conclusion is that:

Teaching is the art of changing the brain.

Zull spends the bulk of the 250 pages exploring the biology and practice behind “creating conditions that lead to change in a learner’s brain.†He provides a list of ten strategies (page 129), based upon the biology of the brain, which can help in making those changes. These strategies apply to parents who are trying to parent, as well as to our own learning process, for ideally we are all life-long learners.

1. Watch for inherent networks (natural talents) and encourage their practice.

2. Repeat, repeat, repeat!

3. Arrange for “firing together.†Associated things should happen together.

4. Focus on sensory input that is “errorless.â€Â

5. Don’t stress mistakes. Don’t reinforce neuronal networks that aren’t useful.

6. Try to understand existing networks and build on them. Nothing is new.

7. Misconnected networks are most often just incomplete. Try to add to them.

8. Be careful about resurrecting old networks; error dies hard.

9. Construct metaphors and insist that your students build their own metaphors.

10. Use analogies and similes, too.

From my own teaching experience, I know these strategies are well worth utilizing. However, implementing them may not always be so easy due to constraints of typical class schedules (insufficient time) or class sizes (too many students), or ingrained habits (for example, viewing mistakes through a negative lens). However, I believe these strategies can aid students in learning about how they learn and engaging in metacognition. In the final analysis, if students understand how they learn, they can take responsibility for their own learning, thus changing their brains through their own efforts.

This is a book that can be read comfortably, and you will progress through the four stages of the learning cycle as you take in the words and ideas (gathering data), reflect on how they can impact yours and your student’s teaching and learning process (reflection), consider how you might alter something about what you do (create an hypotheses), and try out that idea (active testing). Of course, trying out your idea will lead to a new experience, which you will take in and reflect on, perhaps causing you to make a change … And the cycle continues.

For more about James Zull:

- James Zull in his own words – New Horizons for Learning article: What is “The Art of Changing the Brain?â€Â, May 2003

— SharpBrains interview with James Zull: An ape can do this. Can we not?, October 2006

For more about David Kolb:

- Kolb’s faculty page at Case Western

Laurie Bartels writes the Neurons Firing blog to create for herself the “the graduate course I’d love to take if it existed as a program”. She is the K‑8 Computer Coordinator and Technology Training Coordinator at Rye Country Day School in Rye, New York. She is also the organizer of Digital Wave annual summer professional development, and a frequent attendee of Learning & The Brain conferences.

Laurie Bartels writes the Neurons Firing blog to create for herself the “the graduate course I’d love to take if it existed as a program”. She is the K‑8 Computer Coordinator and Technology Training Coordinator at Rye Country Day School in Rye, New York. She is also the organizer of Digital Wave annual summer professional development, and a frequent attendee of Learning & The Brain conferences.

Laurie, thanks for reviewing Zull’s book. Clearly a boon for those who follow linear, empiric models of inquiry.

How about his thoughts on non-linear empiric or networking learning?

M. A. Greenstein

Founding Director, The George Greenstein Institute for the Advancement of Somatic Arts and Science

Hello M.A., I had the fortune to read Zull’s book too, and am a bit mystified by your comment. He is a biologist and educator, so his perspective (as ours) is brain-based, research-based. Research has little to do with linear/ non-linear, and networked or not. In fact, many of his points, as reflected in Laurie’s review, are non-linear (use of metaphors, analogies), and empathize the role of neuronal networks.

Our brain is our brain is our brain. we don’t impose on it our views on how it works/ should work, but we try to understand what is in fact going on so we can all benefit from that knowledge. Zull’s is a masterful book in that regard.

Alvaro and Sharpbrains community, allow me to clarify the point of my question.

First, I was responding to Laurie’s linear layout of Zull’s/Kolb’s cycle, especially in light of scientific procedure. (Ah, the limits of discursive writing.)

My understanding from reading deeply in the area of neuro and cognitive science is that while models of cognitive process are still debated, one illuminating paradigm speaks of a non-linear, “emergent” picture of learning. In my view, Laurie’s review, while generous in coverage, did not address that perspective.

Second, my question stems from years of teaching research methods in the arts and humanities. Both students and I recognize the value of phenomenological and empirical inquiry, though visual and performing art students show great leanings toward non-empiric, non-phenomenological methods, characterized by my Cal Tech colleagues as “fuzzy logic”, i.e., they’ll rely on diffused, syncretic hunches or intuitive cross-referential approaches to both deductive and inductive inquiry. Please note, by using these terms, I am not suggesting a return to an old, outmoded rational/irrational picture of human psychology. I’m simply pointing out what the Sharpbrains community already knows: different disciplines require different learning strategies.

Third, I agree, “our brain is our brain,” but would you not agree, that the pictures and theories we form about how the brain works influences the process of brain research? e.g., systems of representation like neural networking, right/left brain correspondence theory? The brain makes culture and culture makes the brain. Oui?

Finally, Zull’s four stages are quite familiar to those of us raised on the brain/mind science of creativity. I applaud his efforts to update the biology of the learning/creative process.

Again, grateful for Laurie’s review and for the chance to debate critical questions for 21st century education.

Respectfully,

M. A.

Hello M.A, thank you for that excellent clarification.

Let me first emphasize the value of that cycle: what Zull and others found out, and he explains very well, is that our brain goes exactly through that sequence of steps while learning (at least with the activities that were tested). Judgements such as “that is linear” may not help appreciate that reality, that finding, and discuss potential implications.

Now, you are right that brain research (which has been around for perhaps a century, with neuroimaging only for 10–20 years) can only help understand a small portion of learning and teaching (which has of course been around as a species for a while longer…)

I also do agree with “The brain makes culture and culture makes the brain”. Science advanced with hypotheses and with testing, gaining ground cumulatively. The work that Laurie reviews is but a step in that direction. There are many others.

Again, thank you for your thoughtful comment.

I haven’t read the book, but “Teaching is the art of changing the brain”? That’s the conclusion, really? I mean, if students are to learn at all the brain has to change. Indeed, if you’ve read this comment, I’ve just “changed your brain”. The conclusion, in other words, is utterly trivial given modern cognitive science and the computational theory of mind…

Hi Michael,

Yes, anything and everything in which we engage can change our brains. Indeed, most teachers are hoping for change that lasts and is substantive, not superficial. However, I am willing to bet most teachers do not consciously stop to think about what they do in terms of physically changing the brain of the learner.

Zull’s book does an exemplary job of explaining what happens in the brain as it learns and changes. Teachers appreciate tools and explanations that are useful, understandable and immediately applicable. By placing the biological results of learning front and center, Zull provides an account of what is happening in the brain, giving teachers an insight into the (hoped for) results of their efforts. This may help some understand why what they do works, and may provide others with a fresh toolbox for figuring out ways to make an impact on a learner’s brain.

The conclusion may seem trivial to those well-versed in biology, but to those whose lens is filtered by a room full of children or young adults, thinking of teaching as the art of changing the brain may seem rather empowering.

Regards,

Laurie

Laurie’s comments seem to align with a quibble I had: teaching is the art of trying to change the brain.

Learning is the art of changing the brain. Teachers (and trainers and mentors) can certainly take advantage of research to increase the likelihood of the change — but the brain making and strengthening connections isn’t in the teacher’s head.

(Well, okay, the teacher’s learning, too, we hope…)

In the organizational and corporate world, alas, there’s still a lot of reliance on the Little Red Schoolhouse approach to skill and knowledge in the workplace. Having more people read books like Zull’s may help overcome that.

Michael, Laurie, Dave, thank you for creating a superb conversation that reflects our effort to converse across several disciplines: cognitive science, medicine, education, training. We need many more exchanges like this!