Try Thinking and Learning Without Working Memory

Imagine dialing a phone number by having to look up each digit one at a time in the phone book. Normally, you look up the number and remember all seven digits long enough to get it dialed. Even with one digit at a time, you would have to remember each digit long enough to get it dialed. What if your brain could not even do that! We call this kind of remembering, “working memory,” because that is what the brain works with. Working memory is critical to everyday living.

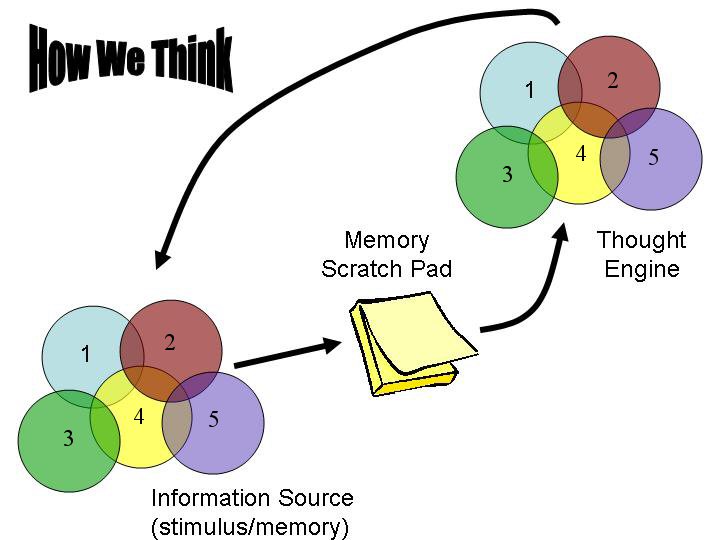

Conscious thought involves moving a succession of items through what seems like a virtual scratch-pad. Think of it like streaming audio/video, where “thought bites” move on to the scratch pad where they are fed into a thought process and then moved off the scratch pad to make room for the next thought bite.

We think with what is in working or “scratch pad” memory. What we know, stored in regular memory, is brought onto the scratch pad in successive stages, each involving subjecting the knowledge to analysis, integration into the current context, and creative re-organization via our thinking processes (“thought engine”). The animated version of this graphic shows item 1 moving on to the scratch pad and then sent on to the “thought engine.” This is followed by item 2, then 3, etc.

Conscious thinking thus requires the ability to hold information “on line” long enough to use it in thinking. Conscious thought thus seems to be a serially ordered process of moving thought bites on to and off of the scratch pad.

Unconscious Thinking

What about unconscious thought … the kind that occurs when you are not paying attention? We know that the subconscious mind is processing information (i.e. “thinking”) all the time, even while we sleep. The evidence for this kind of “sleep learning” is incontrovertible and summarized in my memory improvement book (see http://thankyoubrain.com). Subconscious thinking and its related memories may not involve a scratch pad of working memory. Subconscious thinking could occur as multiple parallel processes and may be more non-linear than conscious thought. However, in the case of dream sleep, which I regard as a form of consciousness, those dreams that I happen to remember do seem to be based on serially ordered “thought bites.”

A recent study, not explicitly concerning memory, sheds some important light both on how we think and on the role of working memory in thought. In this study, the researchers examined how people make a correct choice. Researchers compared the quality of decisions formed from conscious versus unconscious thinking with that resulting from unconscious thinking. Here is how they studied this issue. In one study, subjects were given information about the attributes of four hypothetical cars, and they were to decide which was the best car, based on the attributes assigned to each car. Analysis conditions were either simple (based on only four attributes) or complex (based on 12 attributes). After reading about the attributes, subjects were assigned to one of two groups: conscious analysis or to an unconscious thought condition. In the conscious condition, they thought about the attributes for four minutes before making a choice. In the unconscious condition, subjects were told they would have to make a choice in four minutes, but they were distracted during that time by being required to solve anagrams.

Their “thinking” about the problem was thus not allowed to be conscious.

Not surprisingly, when only four attributes were involved, subjects in the conscious-thought condition made the best choice of car. But when the complex condition of 12 attributes, results reversed. The best car was chosen most reliably in the unconscious-thought condition.

In a second study, one change was made. Instead of choosing the best car, subjects were asked about their attitudes toward the four cars. Again, conscious thinkers made the clearest distinctions among the cars when only four attributes were considered, but the opposite occurred when 12 attributes had to be considered.

In another experiment, two stores were selected, one that sold complicated items like furniture and the other a department store that sold simple products. As people left the store, people were asked questions about what they bought, why they bought it, how costly was it, and how much they thought about making the choice. The buyers were categorized as either “thinkers” (those who spent a lot of time consciously making a decision) and “impulse buyers” (who did not spend much time consciously thinking about their choice). Several weeks later, these same people were called to check on how satisfied they were with the purchase. As expected, more post-choice satisfaction was found in the conscious thinker group, but only for the simple items in the department store. For the complex choices in the furniture store, the unconscious thinkers expressed the most satisfaction with their purchases.

What all this says is that simple decisions are best made by careful conscious thought. But for complicated decisions, the best choices may result from “deliberation without paying attention,” that is letting the thinking be done by the unconscious mind. I interpret these results to reflect the dependence of conscious thought on scratch-pad memory and the relative independence of subconscious thought on scratch-pad memory. Conscious thought is very effective as long as it can work on information that it can hold on-line in working memory. But working memory has limited capacity. Therefore it cannot be very effective when the amount of information needed for high-quality thought exceeds the carrying capacity of working memory.

The corollary of this new evidence about working memory and thinking processes is that if we had a bigger working memory, we might think better.

Working Memory Load Affects Paying Attention

Paying attention is pre-requisite to learning. The ability to pay attention seems to be affected by how much information (load) is being carried in working memory. These principles have been elucidated in human experiments that tested the assumption that attending to relevant details in a learning situation requires that the details be held in working memory. Having other, non-relevant, information in working memory at the same time serves as a distraction, lowering attention and interfering with memory formation.

In this experiment, participants performed an attention task that required them to ignore pictures of distracter faces while holding in working memory a string of digits that were in the same order (low memory load) or different order (high memory order) on every trial. The test thus was one of multi-tasking, one task being holding the digits in working memory and the other task being identifying whether a name flashed on the screen was that of a famous politician or a pop star, while a contradictory face was projected. For example, the name Mick Jagger would have the face of Bill Clinton superimposed, and the task was to know that Mick Jagger is a pop star, not a politician.

The attention performance degraded severely with high working-memory load. That is, the distracting faces created confusion when subjects were also required to hold mixed-order digits in working memory at the same time.

The point is simple. It is hard to think about two complicated things at once. The growing trend, especially among young people, to multi-task may seem wonderful. But actually, multi-tasking is most likely to interfere with focused attention and, in turn, degrade memory formation, recall, and thinking quality.

Training Working Memory and IQ

Studies have shown that it is possible to train ADHD children to have better working memories. This led researchers in Japan to try to develop a simple working memory training method and to test whether this method can increase the working memory capacity and whether this has any effect on a child’s IQ. Children ages 6–8 were trained 10 minutes a day each day for two months. The training task to expand working memory capacity consisted of presenting a digit or a word item for a second, with one-second intervals between items. For example, a sequence might be 5, 8, 4, 7, with one-second intervals between each digit. Test for recall could take the form of “Where in the sequence was the 4?” or “What was the third item?” Thus students had to practice holding the item sequence in working memory. With practice, the trainers increased the number of items from 3 to 8.

After training, researchers tested the children on another working memory task. Scores on this test indicated that working memory correlated with IQ test scores. That is, children with better working memory ability also had higher IQs. When first graders were tested for intelligence, the data showed that intelligence scores increased during the year by 6% in controls, but increased by 9% in the group that had been given the memory training. The memory training effect was even more evident in the second graders, with a 12% gain in intelligence score in the memory trained group, compared with a 6% gain in controls. As might be expected, the lower IQ children showed the greatest gain from memory training.

So in conclusion, it seems that working memory capacity can be increased by training and that such training can even raise IQ, at least in young children.

Benefits of Increasing Working Memory

Accumulating evidence seems to indicate that working memory, with proper training, can be improved in anyone, even adults. I recently found a research report in which lasting improvements in brain function were produced in healthy adults by only five weeks of practice on three working-memory tasks that involved the location of objects in space. Subjects performed 90 trials per day on a training regimen (CogMed). MRI scans showed increased activity in the cortical areas that were involved in processing the visual stimuli. Brain activity increases in these areas appeared within the first week and grew over time.

Similar results have been reported by other investigators. In a few cases, where different kinds of stimuli were used, memory training induced a decrease of brain activity in certain areas, which is interpreted to indicate that the trained brain did not have to work as hard. While we clearly don’t understand things very well, it seems clear that working memory training not only improves memory capability but also causes lasting changes in the brain.

Help Your Working-Memory Capacity

I just read a fascinating book on increasing teacher awareness of the importance of working-memory capacity for teaching and learning strategies. Many youngsters have working memory limitations, and they usually do not grow out of them. This is a major and serious cause of low grades, poor learning skills, poor confidence, and life-long diminished motivation to learn.

Limited working-memory capacity impairs the ability to think and solve problems. I was told once by a middle-school teacher that her “special needs” students could do the same math as regular students, but they just can’t remember all the steps. This clearly reflects a limited working-memory capacity. If the demands made on working memory could be lessened, better thinking could result.

Certain strategies can help to reduce the load on working memory. Teachers should model and students should employ the following devices:

- Provide help, cues, mnemonics, reminders.

- KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid!)(example: use short, simple sentences, present much of the instruction as pictures/diagrams).

- Don’t present so much information. Less can be more.

- Facilitate rehearsal, using only relevant information and no distractors.

- Get engaged, by taking notes, and creating diagrams and concept maps.

- Attach meaning from what is already known. (The more you know, the more you can know).

- Organize information in small categories.

- Break down tasks into small chunks. Master each chunk sequentially, one at a time.

Doing these things not only helps the thinking process, but will also promote the formation of lasting memories. The process of converting working memory into permanent form is called consolidation, and I will explain that next time.

— W. R. (Bill) Klemm, D.V.M., Ph.D. Scientist, professor, author, speaker As a professor of Neuroscience at Texas A&M University, Bill has taught about the brain and behavior at all levels, from freshmen, to seniors, to graduate students to post-docs. His recent books include Thank You Brain For All You Remember and Core Ideas in Neuroscience.

— W. R. (Bill) Klemm, D.V.M., Ph.D. Scientist, professor, author, speaker As a professor of Neuroscience at Texas A&M University, Bill has taught about the brain and behavior at all levels, from freshmen, to seniors, to graduate students to post-docs. His recent books include Thank You Brain For All You Remember and Core Ideas in Neuroscience.

Related articles on Working Memory Training

- Can Intelligence Be Trained? Martin Buschkuehl shows how

- Working Memory Training: Interview with Dr. Torkel Klingberg

Sources

1. Repovs, G and Bresjanac, M. 2006. Cognitive neuroscience of working memory: a prologue. Neuroscience. 139: 1–3.

2. Dijksterhuis, A. et al. 2006. On making the right choice: the deliberation-without-attention effect. Science. 311: 1005–1007.

3. Wajima, Kayo, and Sawaguchi, T. 2005. The effect of working memory training on general intelligence in children. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. Abstract 772.11.

4. de Fockert, J. W. et al. 2001. The role of working memory in visual selective attention. Science. 291: 1803–1806.

5. Olesen, P. J., Westerberg, H., and Kingberg, T. 2004. Increased prefrontal and parietal activity after training of working memory. Nature Neuroscience. 7: 75–79.

6. Gathercole, Susan E., and Alloway, Tracy P. 2008. Working Memory and Learning. Sage Publications, 124 pages.

7. Gathercole, Susan E., and Alloway, Tracy P. 2008. Working memory and learning. Sage Publications, . 124 pages.

Here is an interesting interview with a woman who claims that she can not forget:

http://scienceblogs.com/neurophilosophy/2008/05/an_interview_with_the_woman_wh.php

Charles

After reading this article and a few others, I looked at the Cogmed website. Cogmed purports to help people improve working memory and attention and reduce impulsive behavior.

Ironically, the first page I clicked on had a careless grammatical error or typo that made the page difficult to read — “Cogmed Working Memory Training is developed help people with sustainably improve working memory and attention.”

It must have passed through the hands of many inattentive staff members before appearing online. Perhaps they could benefit from using their own product!

http://www.cogmed.com/cogmed/sections/en/9.aspx

I’m very interested in software for improving my memory, but I won’t patronize a business that does such sloppy work, because I fear it carries over into all aspects of the product.

Thank you Mary…I am sure the Cogmed folks would appreciate if you let them know about that, so they can fix it.

And I encourage you to take a more substantial look at programs that may help, using for example our 10-question checklist

https://sharpbrains.com/resources/10-question-evaluation-checklist/

This list of published scientific studies may well be more meaningful than one typo

http://www.cogmed.com/cogmed/articles/46.aspx

Please remember no intervention is best for everyone, so you do well in continuing your research.

An interesting study with the promise of considerable and exciting work for the future.

I found myself speculating as I read through the arguments as to whether there’s a definable gender-based difference in working memory capacity and performance capabilities.

Is there any research in this area?

Hello David,

There is significant variability among individuals, regardless of gender, which does impact performance.

I haven’t come across meaningful data defining gender-based WM differences. Pls let us know if you find any.

“If you have enough working memory to both be processing this information and developing your own thoughts, you may be thinking now, a) what exactly is Working Memory?, and b) why do we even care?.”

nice to know that :). thnx