Dr. Judith Beck on how to Train Your Brain to Think Like a Thin Person

(Brain Fitness doesn’t require the use of expensive equipment. Your brain is enough. Today, as part of our research for The SharpBrains Guide to Brain Fitness, we are honored to interview Dr. Judith Beck on how cognitive techniques can be applied to improve our health and our lives)

(Brain Fitness doesn’t require the use of expensive equipment. Your brain is enough. Today, as part of our research for The SharpBrains Guide to Brain Fitness, we are honored to interview Dr. Judith Beck on how cognitive techniques can be applied to improve our health and our lives)

Dr. Judith Beck is the Director of the Beck Institute for Cognitive Therapy and Research, Clinical Associate Professor of Psychology in Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, and author of Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. Her most recent book is The Beck Diet Solution: Train Your Brain to Think Like a Thin Person.

Dr. Beck, thanks for your time. What does the Beck Institute do?

We have 3 main activities. One, we train practitioners and researchers through a variety of training programs. Two, we provide clinical care. Three, we are involved in research on cognitive therapy.

Please explain cognitive therapy in a few sentences

Cognitive therapy, as developed by my father Aaron Beck, is a comprehensive system of psychotherapy, based on the idea that the way people perceive their experience influences their emotional, behavioral, and physiological responses. Part of what we do is to help people solve the problems they are facing today. We also teach them cognitive and behavioral skills to modify their dysfunctional thinking and actions.

I understand that cognitive therapy has been tested for many years in a variety of clinical applications. What motivated you to bring those techniques to the weight-loss field by writing The Beck Diet Solution?

Since the beginning, I have primarily treated psychiatric outpatients with a variety of diagnoses, especially depression and anxiety. Some patients expressed weight loss as a secondary goal in treatment. I found that many of the same cognitive and behavioral techniques that helped them overcome their other problems could also help them to lose weight‚ and to keep it off.

I became particularly interested in the problem of overweight and was able to identify specific mindsets or cognitions about food, eating, hunger, craving, perfectionism, helplessness, self-image, unfairness, deprivation, and others, that needed to be targeted to help them reach their goal.

What research results back your finding that those techniques help?

Probably the best published study so far is the randomized controlled study by Karolinska Institute’s Stahre and Halstrom (2005, reference below). The results were striking: nearly all 65 patients completed the program and this short-term intervention (10-week, 30-hours) showed significant long-term weight reduction, even larger (when compared to the 40 individuals in the control group) after 18 months than right after the 10-weeks program.

That sounds impressive. Can you explain what makes this approach so effective?

A unique feature is that the book doesn’t offer a diet but does provide tools to develop the mindset that is required for sustainable success, for modifying sabotaging thoughts and behaviors that typically follow people’s initial good intentions. I help dieters acquire new skills. We have sold over 70,000 books so far, and are planning to release a companion workbook this month to further help readers implement the 6‑week program and track progress.

So, in a sense, we could say that your book is complementary to all other diet books.

Exactly. It will help readers at setting and reaching their long-term goals, assuming that the diet is healthy, nutritious, and well-balanced.

The main message of cognitive therapy overall, and its application in the diet world, is straight-forward: problems losing weight are not one’s fault. Problems simply reflect lack of skills–skills that can be acquired and mastered through practice. Dieters who read the book or workbook learn a new cognitive or behavioral skill every day for six weeks. They practice some skills just once; they automatically incorporate others for their lifetime.

What are the cognitive and emotional skills and habits that dieters need to train, and where your book helps?

Great question. That is exactly my goal: to show how everyone can learn some critical skills. The key ones are:

1) How to motivate oneself. The first task that dieters do is to write a list of the 15 of 20 reasons why they want to lose weight and read that list every single day.

2) Plan in advance and self-monitor behavior. A typical reason for diet failure is a strong preference for spontaneity. I ask people to prepare a plan and then I teach them the skills to stick to it.

3) Overcome sabotaging thoughts. Dieters have hundreds and hundreds of thoughts that lead them to engage in unhelpful eating behavior. I have dieters read cards that remind them of key points, e.g., that it isn’t worth the few moments of pleasure they all get from eating something they hadn’t planned and that they’ll feel badly afterwards; that they can’t eat whatever they want, whenever they want, in whatever quantity they want, and still be thinner; that the scale is not supposed to go down every single day; that they deserve credit for each helpful eating behavior they engage in, to name just a few.

4) Tolerate hunger and craving. Overweight people often confuse the two. You experience hunger when your stomach feels empty. Craving is an urge to eat, usually experienced in the mouth or throat, even if your stomach is full.

When do people experience cravings?

Triggers can be environmental (seeing or smelling food), biological (hormonal changes), social (being with others who are eating), mental (thinking about or imagining tempting food), or emotional (wanting to soothe yourself when you are upset). The trigger itself is less important than what you do about it. Dieters need to learn exactly what to say to themselves and what to do when they have cravings so they can wait until their next planned meal or snack.

How can people learn that they don’t have to eat in response to hunger or craving?

I ask dieters, once they get medical clearance, to skip lunch one day, not eating between breakfast and dinner. Just doing this exercise once proves to dieters that hunger is never an emergency, that it is tolerable, that it doesn’t keep getting worse, but instead, comes and goes, and that they don’t need to “fix” their usually mild discomfort by eating. It helps them lose their fear of hunger. They also learn alternative actions to help them change their focus of attention. Feel hungry? Well, try calling a friend, taking a walk, playing a computer game, doing some email, reading a diet book, surfing the net, brushing your teeth, doing a puzzle. My ultimate goal is to train the dieter to resist temptations by firmly saying “No choice”, to themselves, then naturally turning their attention back to what they had been doing or engaging in whatever activity comes next.

You said earlier that some cravings follow an emotional reaction to stressful situations. Can you elaborate on that, and explain how cognitive techniques help?

In the short term, the most effective way is to identify the problem and try to solve it. If there is nothing you can do at the moment, call a friend, do deep breathing or relaxation exercises, take a walk to clear your mind, or distract yourself in another way. Read a card that reminds you that you all certainly not be able to lose weight or keep it off if you constantly turn to food to comfort yourself when you are upset. People without weight problems generally don’t turn to food when they are upset. Dieters can learn to do other things, too.

And in the long term, I encourage people to examine and change their underlying beliefs and internal rules. Many people, for example, want to do everything (and expect others to do everything) in a perfect way 100% of the time, and that is simply impossible. This kind of thinking leads to stress.

The title of the book includes a train your brain promise. Can you tell us a bit about the growing literature that analyzes the neurobiological impact of cognitive therapy?

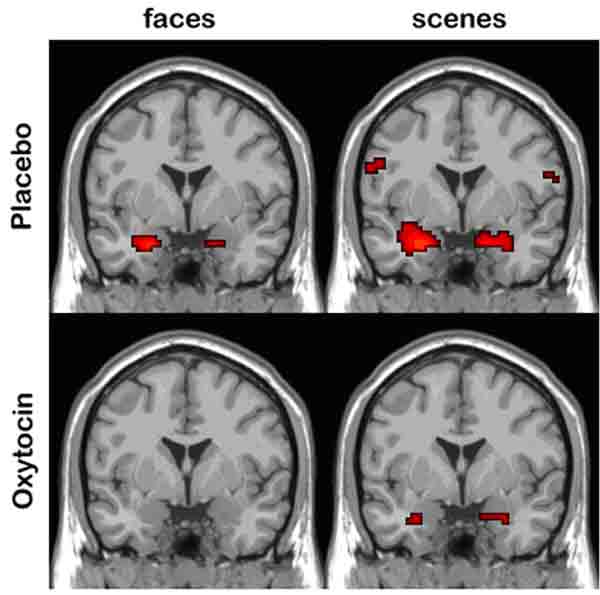

Yes, that is a very exciting area. For years, we could only measure the impact of cognitive therapy based on psychological assessments. Today, thanks to fMRI and other neuroimaging techniques, we are starting to understand the impact our actions can have on specific parts of the brain.

For example, take spider phobia. In a 2003 paper (reference below) scientists observed how, prior to the therapy, the fear induced by viewing film clips depicting spiders was correlated with significant activation of specific brain areas, like the amygdala. After the intervention was complete (one three-hour group session per week, for four weeks), viewing the same spider films did not provoke activation of those areas. Those individuals were able to “train their brains and managed to reduce the brain response that typically triggers automatic stress responses. And we are talking about adults.

Dr. Beck, that is exactly what we find most exciting about this emerging field of neuroplasticity: the awareness that we can improve our lives by refining, training our brains, and the growing research behind a number of tools such as cognitive therapy. Thanks a lot for sharing your thoughts with us.

My pleasure.

————————–

Research Papers mentioned:

Stahre L, Hallstrom T. (2005). “A short-term cognitive group treatment program gives substantial weight reduction up to 18 months from the end of treatment. A randomized controlled trial” Eating and Weight Disorders. 2005 Mar;10(1):51–8.

Paquette, V., Levesque, J., Mensour, B., Leroux, J. M., Beaudoin, G., Bourgouin, P., et al. (2003). Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on the neural correlates of spider phobia. Neuroimage, 18, 401–409.