Non-invasive Transcranial Electrical Stimulation (TES) shows early promise to treat ADHD symptoms in children

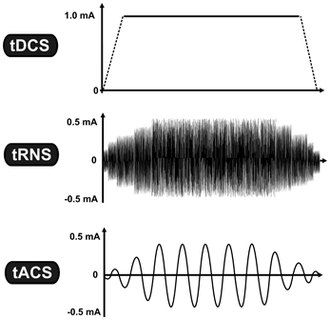

While tDCS uses constant current intensity, tRNS and tACS use oscillating current. The vertical axis represents the current intensity in milliamp (mA), while the horizontal axis illustrates the time-course. Source: Wikipedia.

Many children with ADHD benefit from medication treatment, behavioral treatment, or their combination, but others do not. In addition, parents are often reluctant to start their child on medication and high quality behavioral treatments are not readily accessible in many areas. The long-term efficacy of these treatments is also less than desirable. Thus, despite these evidence-based ADHD treatments, there is a pressing need to develop novel treatments with strong research support.

A study published recently in Translational Psychiatry [Dakawar-Kawar et al (2023). Transcranial random noise stimulation combined with cognitive training for treating ADHD: a randomized sham-controlled trial.] reports promising results for a novel ADHD treatment approach.

The Study:

Study participants were 24 6–12 year-old children recently diagnosed with ADHD following a comprehensive evaluation. They were randomly assigned to receive either a) a type of Transcranial Electrical Stimulation (TES) called Transcranial Random Noise Stimulation (TRNS) or b) sham stimulation; children in both groups engaged in computerized cognitive training during the sessions.

In Transcranial Electrical Stimulation (TES), a weak electric current is delivered to the brain via scalp electrodes, creating an electric field that modulates neuronal activity. The safety profile of this procedure is excellent and side effects are minimal. The theory behind TES as an ADHD treatment is that it may help normalize neuronal activity in youth with ADHD, and thus diminish their symptoms., particularly attention problems.

Cognitive training was combined with TRNS based on the hypothesis that having youth engaged in active cognitive training during stimulation may enhance the benefits of stimulation. The computerized cognitive training program used in this study was called ACTIVATE.

Participants completed 20 minutes sessions per day for 10 days across a 2‑week period. Researchers who conducted the sessions were blind to whether participants received actual TRNS or sham stimulation. Participants and their parents were also kept blind to condition. When parents were asked after the study whether their child had received active or sham treatment, they did no better than chance at identifying their child’s condition.

The Results:

The primary outcome for the study was the ADHD rating scale, a standardized and widely-used behavior rating scale of ADHD symptoms. Parents completed this before treatment began, immediately following the 2‑week treatment, and again 3 weeks later so that the duration of any benefits could be assessed.

Following treatment, ADHD symptom ratings provided by parents were significantly lower for the TRNS group (including cognitive training) compared to the sham treatment group (including cognitive training), controlling for baseline scores. These differences remained evident 3 weeks after treatment ended.

Using a 30% reduction in symptoms from baseline as an indicator of positive treatment response, 55% of the TRNS group were responders compared to only 17% in the sham group. At the 3‑week followup, the percent of responders were 64% and 33% respectively.

Summary and implications:

This is the first study to examine a specific type of transcranial electrical stimulation called TRNS as a treatment for children with ADHD. As discussed above, promising result were obtained in that children receiving active treatment showed significant reductions in parent-rated ADHD symptoms compared to those who received sham treatment. This is an encouraging finding. Furthermore, these differences persisted across the 3‑week followup.

A strength of this study is that it was a true randomized-controlled trial in which research staff providing the treatment, participants, and parents were all blind to condition. Furthermore, the authors confirmed that parents were no better than chance in guessing which condition their child was in. The study would thus be considered to have utilized a gold-standard design ito evaluate this novel treatment.

As the authors themselves note, however, these results should be considered preliminary and require replication with a substantially larger sample than the 24 youth who participated here. This is required before any conclusions about the efficacy of this approach can be made.

Subsequent research on this approach would also be strengthened by including teacher reports to hopefully confirm that improvements are also observed in school. Teachers could provide especially valuable information on whether academic performance, a frequent problem in youth with ADHD, is positively impacted by treatment.

It would also be useful to know whether the cognitive training which accompanied TRNS sessions in this study are necessary for any benefits to occur. This could be done by including additional groups in which stimulation is provided without the cognitive training employed here.

While certainly not conclusive, results from this interesting study are sufficiently promising to warrant a larger randomized controlled trial. Hpefully, results from such a study will become available soon.

– Dr. David Rabiner is a child clinical psychologist and Director of Undergraduate Studies in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at Duke University. He publishes the Attention Research Update, an online newsletter that helps parents, professionals, and educators keep up with the latest research on ADHD.

– Dr. David Rabiner is a child clinical psychologist and Director of Undergraduate Studies in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at Duke University. He publishes the Attention Research Update, an online newsletter that helps parents, professionals, and educators keep up with the latest research on ADHD.

The Study in Context:

- Does ADHD treatment enable long-term academic success? (Yes, especially when pharmacological and non-pharma treatments are combined)

- Evidence review: Physical exercise helps boost attention, cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control in children and adolescents with ADHD