Taking your brain vitals: Stories from a techno-optimist inventing the future of human performance

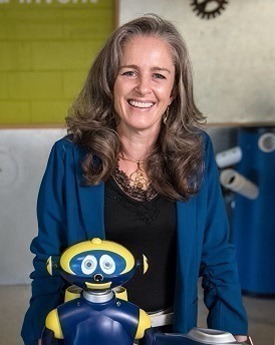

Dr. Cori Lathan, author of Inventing the Future: Stories from a Techno-Optimist

For as long as I can remember, my father loved acting. Into his sixties and early seventies, he was quite active in the theater. He played Tartuffe in Molière’s Tartuffe, Nick Bottom in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and the Old Man in Steve Martin’s Picasso at the Lapin Agile. When he won the role of Scrooge in a local production of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, I was so excited for him that I bought tickets way before opening night. But he was having trouble remembering his lines. Eventually, the director had to let him go.

To find out what was going on, my mom and dad went to his primary care physician, who referred him to a neurologist. After waiting a month for that appointment, the neurologist told Dad to see a neuropsychologist, who was booked another three months out. When that appointment arrived, the neuropsychologist gave him a variety of cognitive tests, including written, verbal, and computer based. After another month, the neurologist called us back in and told my father, “You have mild cognitive impairment.”

“No shit, Sherlock,” I thought. “That’s why we went to see his doctor six months ago.” The neurologist then discussed my father’s other health issues with us, which included cardiovascular disease, sleep apnea, type 2 diabetes, and by that point, depression. I then had an inspiration. “Dad, when was the last time you used your CPAP machine?” He admitted sheepishly, “I don’t use it. I don’t like it.”

“Dad, if your brain doesn’t get oxygen at night, it’s not going to work during the day.” Problem solved. Well, not totally, but it was a start. The real problem was that everything my father was going through—from mental health to chronic illnesses and aging—affects brain health.

In the early 2000s, brain health took center stage in the media. With the release by the NFL Players Association of the first study on the long-term impact of head injuries, concussions became a big topic in both professional and amateur sports. Around the country, parents started questioning whether they should even let their kids play football and soccer. My own daughters participated in sports, and I worried particularly about my fourth grader, a gymnast. Ironically, she got a serious concussion not from doing a backflip but from falling off a piece of playground equipment.

It took her three months to recover. During that time, I learned more about concussion treatment than I ever wanted to know. For someone who likes to analyze and solve problems, I found it particularly distressing that there is no single diagnostic for a concussion. No blood test or imaging technique. Instead, the diagnosis is a subjective determination based on multiple factors:

• Circumstantial (i.e., a recent blow to the head).

• Symptoms (e.g., a headache).

• Impaired balance (as measured by dizziness or stumbling).

• Impaired cognition (as measured by simple verbal questioning).

You’ll note the last three criteria are not very specific to concussion. If the first criterion isn’t met (that is, if you didn’t recently hit your head), a doctor wouldn’t necessarily diagnose concussion as the cause for your symptoms.

By 2010, it was clear that a new approach to brain health was needed. The Navy Bureau of Medicine contracted AnthroTronix to develop a tool to measure the impact of deployment as a whole—not just blast exposure—on cognition. We examined how experts currently measured brain health—like the neurologist who met my dad, gave him some tests, and made a determination. No matter how gifted the neurologist may be, there was no way for him to know whether my dad’s cognition had declined, improved, or stayed the same over the past months or even years. Yet I’d expected that doctor to have all the answers.

We proposed a new approach. Rather than boil the ocean trying to characterize every aspect of cognition, we said, “Let’s track brain health as if it’s a vital sign.” To do this, we needed a tracking tool that was as easy to use as, say, a thermometer or blood pressure cuff. Before you assume this is impossible, think about the way you actually use a thermometer. The readout tells you whether your temperature is high or low, which helps you to form a picture of your overall health. You would never automatically attribute a high number to a particular illness, though a fever is certainly a sign that something may be severely wrong. With a blood pressure cuff, we would never check your pressure once—or even twice—to decide whether you have hypertension.

We would need to track it over time so we have a fuller picture. Having that baseline also helps us determine if a change occurs that is significant for you. For example, I have consistently low blood pressure, so what’s high for me may be normal for you. And if we didn’t have that baseline, a doctor might consider my blood pressure to be fine when in fact it’s elevated for me.

Just as a thermometer reading doesn’t tell you what’s wrong with you, we wouldn’t expect this tool to diagnose a soldier. But like a thermometer, it would quickly and reliably assess meaningful changes in a soldier’s medical status. Other key aspects of our approach were that the tool must work on any mobile platform and be self-administered. Our concept of operations was that a busy medic in the field could give a soldier a handheld device, walk away to do whatever else they needed to do, and come back five minutes later for the answer.

Our team found three tests that met the requirements. All had been used in research for over twenty years, so they were time tested and refined. One measured simple reaction time: when an object appears in the middle of the screen, touch it as quickly as you can. The second measured choice reaction time: when an object appears in the middle of the screen, choose the object below that matches it. The third, a go/no-go game, measured impulsiveness: you are shown an object to target and must touch it as quickly as you can when it appears on-screen (go) and do nothing when a nontarget object appears (no-go).

Our team found three tests that met the requirements. All had been used in research for over twenty years, so they were time tested and refined. One measured simple reaction time: when an object appears in the middle of the screen, touch it as quickly as you can. The second measured choice reaction time: when an object appears in the middle of the screen, choose the object below that matches it. The third, a go/no-go game, measured impulsiveness: you are shown an object to target and must touch it as quickly as you can when it appears on-screen (go) and do nothing when a nontarget object appears (no-go).

Simple, right? They are supposed to be. You shouldn’t need a college education to do well; you just need sustained attention. Our goal was to measure focus or attention and how quickly someone could respond accurately, called processing speed. Attention and processing speed are building blocks for the harder stuff our brains have to do, like remembering instructions or planning steps to complete a task.

Using those three games, we developed an app-based cognitive assessment tool, a “brain vital sign” for military use. We called the app DANA.

As of this writing, we are two years into a study following a cohort of older adults with mild cognitive impairment to see if DANA can detect cognitive changes before a dementia diagnosis. And our work testing the impact of DANA didn’t stop with Alzheimer’s research. We received an additional NIH grant to work with the Johns Hopkins Medicine’s virtual COVID-19 clinic to track recovering patients who might experience diagnosed or undiagnosed “long-haul” symptoms like cognitive impairment. This research is ongoing and will document and hopefully help many people who are struggling with the lingering effects of COVID-19.

My vision for DANA has always been that every time you go to the doctor, in addition to taking your height, weight, blood pressure, and temperature, they will take your DANA brain vital. When measuring your brain health becomes second nature—as common as checking your blood pressure—it will empower everyone, no matter their age, to spot changes sooner and take action.

My vision for DANA has always been that every time you go to the doctor, in addition to taking your height, weight, blood pressure, and temperature, they will take your DANA brain vital. When measuring your brain health becomes second nature—as common as checking your blood pressure—it will empower everyone, no matter their age, to spot changes sooner and take action.

– Dr. Corinna (Cori) Lathan is a technology entrepreneur who has developed robots for kids with disabilities, virtual reality technology for the space station, and wearable sensors for training surgeons and soldiers. Above is an adapted excerpt from her new book, Inventing the Future: Stories from a Techno-Optimist, which explores the many possibilities of tomorrow through Cori’s twenty-year journey inventing at the edge of technology and human performance.