Study finds lifelong neurogenesis in the hippocampus, but rates decline with age and, especially, Alzheimer’s disease

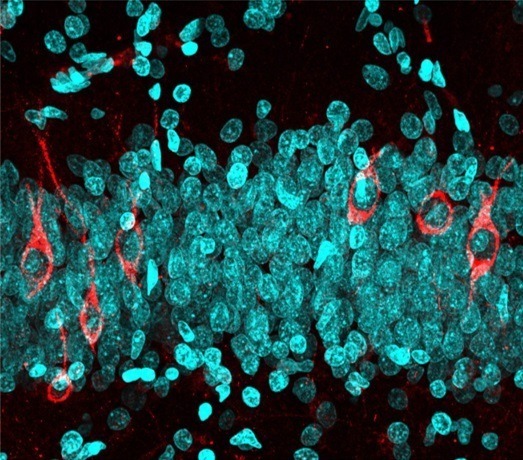

Recent, immature neurons (in red) and older, mature neurons (in blue) in the hippocampus of a 68-year-old’s brain. Credit: CSIC

___

“Reports of old brains’ decrepitude have been greatly exaggerated, scientists reported on Monday, unveiling results that contradict a much-discussed 2018 study and instead support the idea that human gray matter is capable of generating new neurons up to the ninth decade of life.

The research, published in Nature Medicine, also found that old brains from people without dementia have much higher rates of such neurogenesis than do the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease, offering a new clue to a field that is desperate for new ideas…

In a 43-year-old brain, for instance, the scientists measured roughly 42,000 new neurons per cubic millimeter of hippocampus (approximately the volume of nine grains of table salt). An 87-year-old had 20,000 new neurons per cubic millimeter…

Although Llorens-Martín and her colleagues did not have enough brains of the same age to make definitive comparisons of individual neurogenesis rates, they saw hints of person-to-person variation. Among people in their 60s without Alzheimer’s, she said, rates of neurogenesis ranged from about 30,000 to 40,000 new neurons per cubic millimeter of hippocampus; in 80-somethings, it was 20,000 to 30,000.

“If you can increase the rate of neurogenesis, it might be protective” against Alzheimer’s, she said.

The New Study:

Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is abundant in neurologically healthy subjects and drops sharply in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (Nature Medicine). From the abstract:

- The hippocampus is one of the most affected areas in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) … By combining human brain samples obtained under tightly controlled conditions and state-of-the-art tissue processing methods, we identified thousands of immature neurons in the DG of neurologically healthy human subjects up to the ninth decade of life. These neurons exhibited variable degrees of maturation along differentiation stages of AHN (Note: adult hippocampal neurogenesis). In sharp contrast, the number and maturation of these neurons progressively declined as AD advanced. These results demonstrate the persistence of AHN during both physiological and pathological aging in humans and provide evidence for impaired neurogenesis as a potentially relevant mechanism underlying memory deficits in AD that might be amenable to novel therapeutic strategies.