Neuroimaging study finds extensive brain rewiring–in just six months–among illiterate adults learning to read and write

Learning to read and write rewires adult brain in six months (New Scientist):

“Learning to read can have profound effects on the wiring of the adult brain – even in regions that aren’t usually associated with reading and writing.

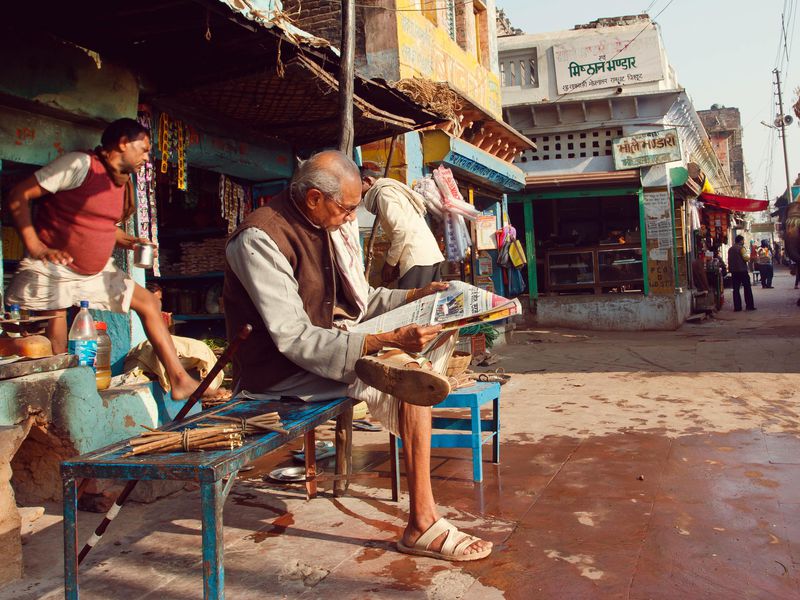

That’s what Michael Skeide of the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany, and his colleagues found when they taught a group of illiterate adults in rural India to read and write…By the end of the study, the team saw significant changes in the brains of the people who had learned to read and write. These individuals showed an increase in brain activity in the cortex, the outermost layer of the brain, which is involved in learning.

Learning to read also seemed to change brain regions that aren’t typically involved in reading, writing or learning. Two regions deep in the brain, in particular, appeared more active after training – portions of the thalamus and the brainstem.

These two regions are known to coordinate information from our senses and our movement, among other things. Both areas made stronger connections to the part of the brain that processes vision after learning to read. The most dramatic changes were seen in those people who progressed the most in their reading and writing skills.”

The Study

Learning to read alters cortico-subcortical cross-talk in the visual system of illiterates (Science Advances)

- Abstract: Learning to read is known to result in a reorganization of the developing cerebral cortex. In this longitudinal resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study in illiterate adults, we show that only 6 months of literacy training can lead to neuroplastic changes in the mature brain. We observed that literacy-induced neuroplasticity is not confined to the cortex but increases the functional connectivity between the occipital lobe and subcortical areas in the midbrain and the thalamus. Individual rates of connectivity increase were significantly related to the individual decoding skill gains. These findings crucially complement current neurobiological concepts of normal and impaired literacy acquisition.