Understand your connectome, understand yourself

—–

—–

NO ROAD, NO trail can penetrate this forest. The long and delicate branches of its trees lie everywhere, choking space with their exuberant growth. No sunbeam can fly a path tortuous enough to navigate the narrow spaces between these entangled branches. All the trees of this dark forest grew from 100 billion seeds planted together. And, all in one day, every tree is destined to die.

This forest is majestic, but also comic and even tragic. It is all of these things. Indeed, sometimes I think it is everything. Every novel and every symphony, every cruel murder and every act of mercy, every love affair and every quarrel, every joke and every sorrow — all these things come from the forest.

You may be surprised to hear that it fits in a container less than one foot in diameter. And that there are seven billion on this earth. You happen to be the caretaker of one, the forest that lives inside your skull. The trees of which I speak are those special cells called neurons. The mission of neuroscience is to explore their enchanted branches — to tame the jungle of the mind.

Neuroscientists have eavesdropped on its sounds, the electrical signals inside the brain. They have revealed its fantastic shapes with meticulous drawings and photos of neurons. But from just a few scattered trees, can we hope to comprehend the totality of the forest?

In the seventeenth century, the French philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal wrote about the vastness of the universe:

Let man contemplate Nature entire in her full and lofty majesty; let him put far from his sight the lowly objects that surround him; let him regard that blazing light, placed like an eternal lamp to illuminate the world; let the earth appear to him but a point within the vast circuit which that star describes; and let him marvel that this immense circumference is itself but a speck from the viewpoint of the stars that move in the firmament.

Shocked and humbled by these thoughts, he confessed that he was terrified by “the eternal silence of these infinite spaces.” Pascal meditated upon outer space, but we need only turn our thoughts inward to feel his dread. Inside every one of our skulls lies an organ so vast in its complexity that it might as well be infinite.

As a neuroscientist myself, I have come to know firsthand Pascal’s feeling of dread. I have also experienced embarrassment. Sometimes I speak to the public about the state of our field. After one such talk, I was pummeled with questions. What causes depression and schizophrenia? What is special about the brain of an Einstein or a Beethoven? How can my child learn to read better? As I failed to give satisfying answers, I could see faces fall. In my shame I finally apologized to the audience. “I’m sorry,” I said. “You thought I’m a professor because I know the answers. Actually I’m a professor because I know how much I don’t know.”

Studying an object as complex as the brain may seem almost futile. The brain’s billions of neurons resemble trees of many species and come in many fantastic shapes. Only the most determined explorers can hope to capture a glimpse of this forest’s interior, and even they see little, and see it poorly. It’s no wonder that the brain remains an enigma. My audience was curious about brains that malfunction or excel, but even the humdrum lacks explanation. Every day we recall the past, perceive the present, and imagine the future. How do our brains accomplish these feats? It’s safe to say that nobody really knows.

Daunted by the brain’s complexity, many neuroscientists have chosen to study animals with drastically fewer neurons than humans. The worm shown in Figure 2 lacks what we’d call a brain. Its neurons are scattered throughout its body rather than centralized in a single organ. Together they form a nervous system containing a mere 300 neurons. That sounds manageable. I’ll wager that even Pascal, with his depressive tendencies, would not have dreaded the forest of C. elegans. (That’s the scientific name for the one-millimeter-long worm.)

Every neuron in this worm has been given a unique name and has a characteristic location and shape. Worms are like precision machines mass-produced in a factory: Each one has a nervous system built from the same set of parts, and the parts are always arranged in the same way.

What’s more, this standardized nervous system has been mapped completely. The result is something like the flight maps we see in the back pages of airline magazines. The four-letter name of each neuron is like the three-letter code for each of the world’s airports. The lines represent connections between neurons, just as lines on a flight map represent routes between cities. We say that two neurons are “connected” if there is a small junction, called a synapse, at a point where the neurons touch. Through the synapse one neuron sends messages to the other.

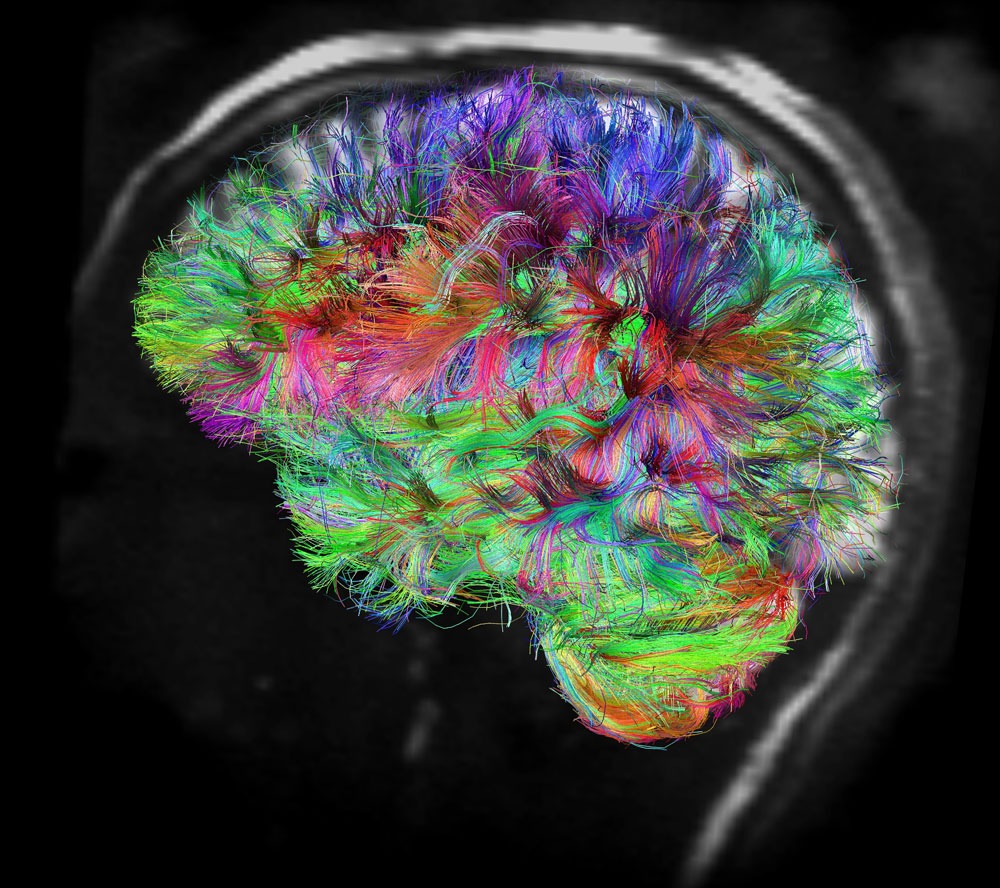

Engineers know that a radio is constructed by wiring together electronic components like resistors, capacitors, and transistors. A nervous system is likewise an assembly of neurons, “wired” together by their slender branches. That’s why the map shown in Figure 3 was originally called a wiring diagram. More recently, a new term has been introduced — connectome. This word invokes not electrical engineering but the field of genomics. You have probably heard that DNA is a long molecule resembling a chain. The individual links of the chain are small molecules called nucleotides, which come in four types denoted by the letters A, C, G, and T. Your genome is the entire sequence of nucleotides in your DNA, or equivalently a long string of letters drawn from this four-letter alphabet.

In the same way, a connectome is the totality of connections between the neurons in a nervous system. The term, like genome, implies completeness. A connectome is not one connection, or even many. It is all of them. In principle, your brain could also be summarized by a diagram that is like the worm’s, though much more complex. Would your connectome reveal anything interesting about you?

The first thing it would reveal is that you are unique. You know this, of course, but it has been surprisingly difficult to pinpoint where, precisely, your uniqueness resides. Your connectome and mine are very different. They are not standardized like those of worms. That’s consistent with the idea that every human is unique in a way that a worm is not (no offense intended to worms!).

Differences fascinate us. When we ask how the brain works, what mostly interests us is why the brains of people work so differently. Why can’t I be more outgoing, like my extroverted friend? Why does my son find reading more difficult than his classmates do? Why is my teenage cousin starting to hear imaginary voices? Why is my mother losing her memory? Why can’t my spouse (or I) be more compassionate and understanding?

This book proposes a simple theory: Minds differ because connectomes differ. The theory is implicit in newspaper headlines like “Autistic Brains Are Wired Differently.” Personality and IQ might also be explained by connectomes. Perhaps even your memories, the most idiosyncratic aspect of your personal identity, could be encoded in your connectome.

Although this theory has been around a long time, neuroscientists still don’t know whether it’s true. But clearly the implications are enormous. If it’s true, then curing mental disorders is ultimately about repairing connectomes. In fact, any kind of personal change — educating yourself, drinking less, saving your marriage — is about changing your connectome.

Although this theory has been around a long time, neuroscientists still don’t know whether it’s true. But clearly the implications are enormous. If it’s true, then curing mental disorders is ultimately about repairing connectomes. In fact, any kind of personal change — educating yourself, drinking less, saving your marriage — is about changing your connectome.

– Sebastian Seung is Professor of Computational Neuroscience and Physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he is currently inventing technologies for mapping connections between the brain’s neurons, and investigating the hypothesis that we are all unique because we are “wired differently.” This article is an excerpt from his book Connectome: How the Brain’s Wiring Makes Us Who We Are.

– Sebastian Seung is Professor of Computational Neuroscience and Physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he is currently inventing technologies for mapping connections between the brain’s neurons, and investigating the hypothesis that we are all unique because we are “wired differently.” This article is an excerpt from his book Connectome: How the Brain’s Wiring Makes Us Who We Are.