Is the University Centered on The Learner or the Professor?

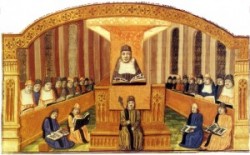

The academic ethos of universities has changed very little since the Middle Ages until the present. However, there is a significant difference between the origin of universities as social institutions and contemporary universities. At first, their structure was more informal and, contrary to what one might think, more flexible. It was students who sought out professors on the basis of their epistemological and deontological authority. The university structure was built upon the studium generale or particulare, which was governed or run by a rector-student who, as in the case of Bologna, was from the Council of Scholars or congregation of students. That is, teaching was based on the individual who learns. Therefore, university institutions were basically centered on that person, that is, the student.

Subsequent modifications were part of a move towards the facultas or ensemble of persons who had the ‘faculty’ of teaching and the ‘faculty’ of administrating teaching on the basis of their epistemological authority. One of the most relevant aspects of the period is the university as a universal, Eurocentric institution, with a common language, Latin, and with a coherent culture – which was not necessarily the best – based on Aristotelian principles influenced by Christianity and aimed at organizing coexistence in society, more in accordance with the system of principles than with the practice. This Medieval culture prescribed behavioral norms through the authority of the Church, but also by means of universities. Let us not forget Stephen Langton, the English priest and councillor of the University of Paris who rooted out tyranny at the University in the early thirteenth century, was later radically opposed to King John of England and was to be one of the authors of the bill of rights, the Magna Carta.

From the fourteenth century onwards, the evolution of the sovereign state and the consequences of the Western Schism weakened the transnational perception of universities and led to more nationalist models, such as those of the universities of Vienna, Heidelberg and Prague. That century marked a new period for universities. Their structure was modified and they began to depend more heavily on the state. In educational terms, there was a move away from meditation on the theme of nature to a utilitarian education. The transition was, however, protracted and complex. For example, surgery and common law remained outside the scope of universities for many years, and physical, chemical and mineral research, which was largely responsible for industrial development, took place outside universities, in the science colleges that existed at the time.

Universities in the Middle Ages later gave rise to models that were increasingly rigid, which had three focal points: the English model or residential university system, such as that of Oxford, the French model of the “grandees écoles” (the so-called Napoleonic system) and the German model of research, which originated at Humboldt University. Mixed models appeared sometime later, including the Chicago model, which followed the English system but with an emphasis on the liberal arts. Universities as we know them today are similar, in a greater or lesser measure, to one of these models or a combination of several of them. Among all of them, the facultas or faculty have been the center of the university structure and have been the quintessential collegiate authority.

Universities in the Middle Ages later gave rise to models that were increasingly rigid, which had three focal points: the English model or residential university system, such as that of Oxford, the French model of the “grandees écoles” (the so-called Napoleonic system) and the German model of research, which originated at Humboldt University. Mixed models appeared sometime later, including the Chicago model, which followed the English system but with an emphasis on the liberal arts. Universities as we know them today are similar, in a greater or lesser measure, to one of these models or a combination of several of them. Among all of them, the facultas or faculty have been the center of the university structure and have been the quintessential collegiate authority.

The schools, departments, institutes and sections are basically organized around the professors and the teaching content that they design, often on an individual basis and in isolation. That is, universities are today centered on the individual who teaches and this is making way for another model taken from the private corporate system in which education is centered on the individual who administers. Both models are in some measure authoritarian, in detriment of the individual who learns, whether this individual is a student, professor or administrator. The backdrop to many university crises has been precisely these dichotomies: the crisis of the relationship between the individual who teaches and the individual who learns, between the member of the ‘academic ethos’ and the member of the ‘social ethos’ and also between the individual who teaches and the one who administers.

Between universities and society, would it not be necessary to replace the academic ethos with an ethos of learning and not by an administrative ethos? If anyone in society requires continuous learning, it is the university community, and particularly professors, given the fact their teaching depends on their constantly learning and renewing their knowledge. This is the objective justification for developing an ethos of learning. But universities, as we shall see in future posts, have been moving in a different direction.

– Miguel Angel Escotet, Ph.D., is a Psychologist, Philosopher, Researcher, and the Dean of the College of Education of the University of Texas at Brownsville. ©2011 Miguel Angel Escotet. All rights reserved. Revised excerpt from M.A. Escotet (2009) University Governance. In Higher Education at Time of Transformation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 126–132. Permission to reprint with appropriate citing.

– Miguel Angel Escotet, Ph.D., is a Psychologist, Philosopher, Researcher, and the Dean of the College of Education of the University of Texas at Brownsville. ©2011 Miguel Angel Escotet. All rights reserved. Revised excerpt from M.A. Escotet (2009) University Governance. In Higher Education at Time of Transformation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 126–132. Permission to reprint with appropriate citing.