Memory Training Reduces Brain Atrophy

Numerous studies show benefits of cognitive training in older adults, despite a recent study questioning their validity. The debate on the effects of specific cognitive interventions is not settled.

Numerous studies show benefits of cognitive training in older adults, despite a recent study questioning their validity. The debate on the effects of specific cognitive interventions is not settled.

A finding that researchers do seem to agree on is that aging is accompanied by brain and cognitive decline. These reductions seem to be modifiable through cognitive and physical exercise. In this vein, our lab recently demonstrated that older adults involved in an 8‑week memory training program show less brain atrophy. This gives some hope for older adults wondering whether their training efforts are really worthwhile.

A major research interest in our lab is how brain structure and memory change across the human life-span. We have recently been able to measure regional changes in the brain within the same older adults over time. In a recent study, my supervisor, Anders Fjell and colleagues found that normal aging Americans (about 60 years old) show regional brain atrophy (shrinkage) of about — 0.5 – 1.0 % after only one year.

The reason why the brain atrophies (shrinks in size) with age is not completely understood. An old myth about aging is that we lose neurons as we age. This does not seem to hold true for healthy older adults. Instead, researchers currently believe that the atrophy is more likely to be driven by 1) nerve cells shrinking and 2) loss of connections between nerve cells

Not only brain size, but also cognitive performance declines as we age. Abilities like processing speed and long-term memory declines steadily. However, the pace of aging varies greatly among older individuals. Thus, a central pursuit in contemporary neuroscience is to undercover modifiers of the aging process.

Various factors are found to be associated with age-related differences in brain structure and cognition. Your genetic makeup seems to be important. Also what socioeconomic background and educational level you have plays a role.

Lately and thoroughly reviewed in the Sharpbrains blog earlier, lifestyle and behavior seem to have a significant impact. One example is nutrition. In fact, David Smith and colleagues in Oxford showed earlier this fall that older adults with mild cognitive impairment have less brain atrophy if they take a vitamin‑B supplement regularly.

Other lifestyle factors contributing to individual age-differences in both brain and cognitive function are physical and mental exercise or brain training. The basis for how these influence the aging process is based on the concept of brain plasticity. Brain plasticity is a multifaceted concept, but can be described as your brain’s ability to change structurally and functionally at any age.

In our lab we were fascinated by this ability and asked the following question: Could memory training impact the brain atrophy that takes place in the aging brain? With this in mind, my research group set out to investigate the effects of a memory training program for healthy middle-aged and older adults (mean age = 60 years).

Through a newspaper add, we recruited more than 40 participants and divided them randomly into a memory training and control group. The memory trainers participated in an 8‑week program where they learned a visual mnemonic technique known as the Method of loci. Using this technique the participants had to learn and recall new verbal information almost everyday, like the names of American presidents, Roman emperors, members of parliament, and the order of countries in South-America.

After 8‑weeks of training, we found that:

a) the memory trainers improved significantly in their ability to remember verbal information in a particular sequence (for instance the name of the 1st or 10th American president). However, they did not improve more on other domains of memory function than the control group, which is in-line with other studies.

b) the thickness of the cerebral cortex increased in several regions of the brain among those who had trained their memory function. Also, participants who had improved the most on the specific memory test where the ones with the most increase in cortical (brain) thickness.

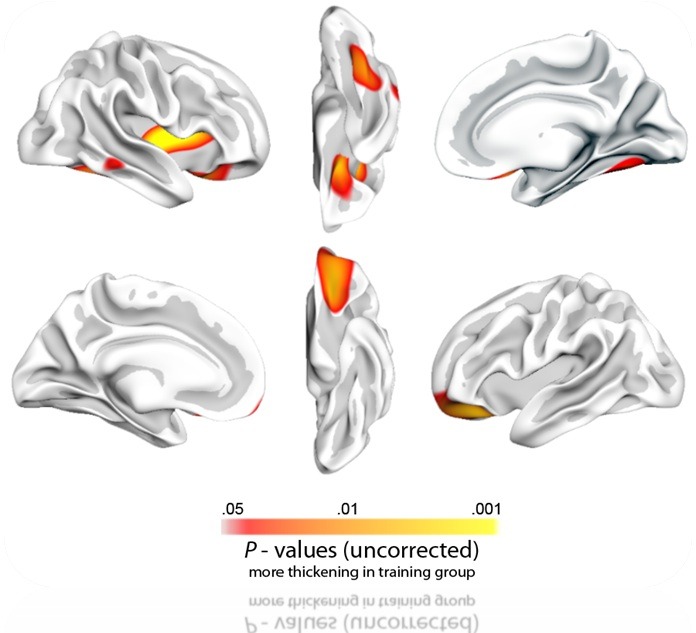

The four regions of the brains in which memory training increased cortical thickness are illustrated below. Two effects were located in the frontal lobes (lateral orbitofrontal cortex), and one in the fusiform region of the right temporal lobe.

Figure 1. The figure show the strength of the effects mapped on a template brain. Top row is the right hemisphere in lateral (from outside), ventral (from under) and medial (from inside) views.

.

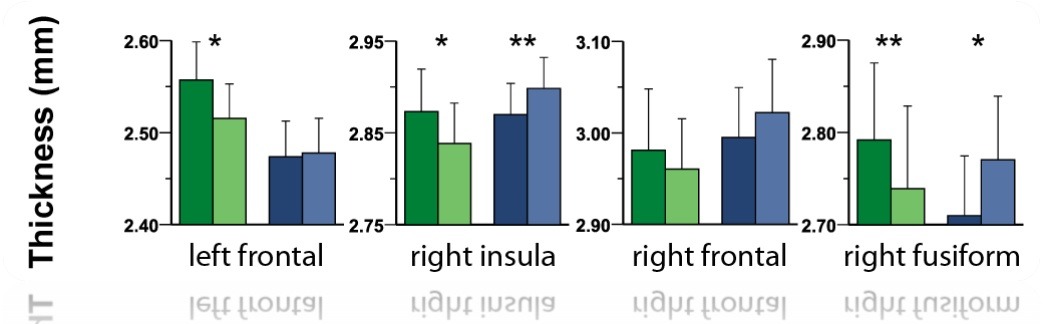

The changes in cortical thickness in the control and training groups are shown in the second figure below. You can see that the control group decreased slightly, whereas the memory trainers increased. Also note that the changes are small (less than 0.05 mm in most areas).

Figure 2. Bar plots of the group-changes in cortical thickness. The green bars are the control group, the blue colors are the training group. Lighter colors are the average thickness at follow-up.

.

What do these findings tell us? It seems as middle-aged and older adults who train their memory vigorously in a 2‑month period have different, more positive changes in brain structure, compared with those who do not. The ones who had better memory improvements also had more positive changes in the brain. The effects on memory performance were positive, but the transfer effect was seen on brain structure only. We did not look at the effects beyond the 2‑months, and we are waiting to see whether cognitive exercise indeed alters the way our brains age in the long-term. Since our study was published, other very recent studies have shown that cognitive exercise in the elderly can also modify the blood flow to, and the underlying nerve fibers (white matter) of the frontal lobes.

Memory training improves specific memory functions, but also seems to make positive changes in the aging brain such as less atrophy and even increased cortical thickness. These results strengthen the conclusions about the value of mental exercise for older adults.

— Andreas Engvig was an intern at Sharpbrains a couple of years ago. He is now a MD-PhD candidate in the Center for the Study of Human Cognition at the University of Oslo, Norway. He is currently pursuing his PhD investigating the effects of memory training on aging brain structures. His first publication recently achieved 8th place in Neuroimage’s “Top 25 Hottest Articles” list.

— Andreas Engvig was an intern at Sharpbrains a couple of years ago. He is now a MD-PhD candidate in the Center for the Study of Human Cognition at the University of Oslo, Norway. He is currently pursuing his PhD investigating the effects of memory training on aging brain structures. His first publication recently achieved 8th place in Neuroimage’s “Top 25 Hottest Articles” list.

References

- Engvig, A., Fjell, A.M., Westlye, L.T., Moberget, T., Sundseth, O., Larsen, V.A., Walhovd, K.B., 2010. Effects of memory training on cortical thickness in the elderly. NeuroImage 52, 1667–1676.

- Engvig, A., Fjell, A.M., Westlye, L.T., Moberget, T., Sundseth, O., Larsen, V.A., Walhovd, K.B., submitted manuscript. Memory training impacts short-term changes in aging white matter.

- Esiri, M.M., 2007. Ageing and the brain. J Pathol 211, 181–187.

- Fjell, A.M., Walhovd, K.B., Fennema-Notestine, C., McEvoy, L.K., Hagler, D.J., Holland, D., Brewer, J.B., Dale, A.M., 2009. One-year brain atrophy evident in healthy aging. J Neurosci 29, 15223–15231.

- Kramer, A.F., Erickson, K.I., 2007. Effects of physical activity on cognition, well-being, and brain: human interventions. Alzheimers Dement 3, S45-51.

- Lamprecht, R., LeDoux, J., 2004. Structural plasticity and memory. Nat Rev Neurosci 5, 45–54.

- Lovden, M., Bodammer, N.C., Kuhn, S., Kaufmann, J., Schutze, H., Tempelmann, C., Heinze, H.J., Duzel, E., Schmiedek, F., Lindenberger, U., 2010. Experience-dependent plasticity of white-matter microstructure extends into old age. Neuropsychologia 48, 3878–3883.

- Mozolic, J.L., Hayasaka, S., Laurienti, P.J., 2010. A cognitive training intervention increases resting cerebral blood flow in healthy older adults. Front Hum Neurosci 4, 16.

- Park, D.C., Reuter-Lorenz, P., 2009. The adaptive brain: aging and neurocognitive scaffolding. Annu Rev Psychol 60, 173–196.

- Reid, L., MacLullich, A., 2006. Subjective Memory Complaints and Cognitive Impairment in Older People. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 22, 471–485.

- Smith, A.D., Smith, S.M., de Jager, C.A., Whitbread, P., Johnston, C., Agacinski, G., Oulhaj, A., Bradley, K.M., Jacoby, R., Refsum, H., 2010. Homocysteine-lowering by B vitamins slows the rate of accelerated brain atrophy in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 5, e12244.

- Valenzuela, M., Sachdev, P., 2009. Can cognitive exercise prevent the onset of dementia? Systematic review of randomized clinical trials with longitudinal follow-up. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 17, 179–187.

My friend, THAT was an EXCELLENT piece! Very well laid out, and the EVIDENCE appears inarguable. So that begs the question, who in their right mind would fail to see the benefits of strategic cognitive training to improve their aging brain after seeing this information? I know I’ll reference this when speaking to people I know who are entering or living in their golden years. Transferability? It’s MEMORY for crying out loud — that is very important! The way I figure it, you throw in a little brain training to help processing speed, tack on some brain training to improve motor skills — all combined with memory training, meditation-related practices, increased social interaction, dancing, etc., and most people should be able enjoy a long term, higher cognitive quality of life.

Thanks! Let me know if you need a pdf of the article. I like your idea of recommending cross-modal brain training to improve cognitive QoL after middle-age.

Cheers,

-A