8‑week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) course found to be as effective as Lexapro (escitalopram) to treat adults with anxiety disorders, and with far fewer side effects

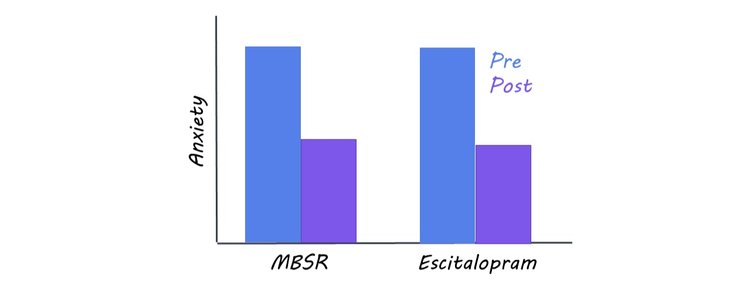

Credit: BrainPost, with data from Hoge et al (2022)

Anxiety is the most common psychiatric disorder, with over 301 million ?people affected around the world. Whether extreme anxiety arises in social situations, is triggered by a particular phobia, or manifests as a general unease in the world, it can severely affect people’s everyday functioning and lead to high levels of distress.

Luckily, there are good treatments for anxiety, including Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (or CBT) and various pharmaceutical drugs. Still, CBT takes a highly-trained therapist to administer and can be lengthy and expensive, making it inaccessible to many people who need it. And, while drug therapies can work well and are often covered by insurers, they may not be acceptable for people who worry about the potential side effects of putting a drug in their body.

Now a new paper suggests an alternative, effective treatment for anxiety sufferers: Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). It adds to the case that health insurers should cover MBSR as a treatment for anxiety (just as other treatments are covered), as long as we bear in mind its limitations.

In this study, 276 patients with an anxiety disorder were randomly assigned to either an eight-week course of MBSR or a well-known anti-anxiety drug, Lexapro (with ongoing monitoring). The MBSR course, developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn, involved introducing people to a variety of meditation practices (like mindful breathing, body scans, walking meditation, and loving-kindness meditation) and having them meditate daily at home to improve their skills. Overall, the training is designed to help people learn how to pay attention to the present moment and accept whatever sensations, thoughts, and feelings arise without judgment.

During the treatment time, people in both groups reported how anxious they felt and whether or not they were experiencing any side effects. Afterwards, they were followed for six months to see how they fared, but without the control of the initial eight-week treatment—meaning, they were free to continue with the drug or meditation, or try another form of treatment.

Results showed that at the end of eight weeks, both groups had equal reductions in their anxiety symptoms, suggesting that MBSR may work as well as Lexapro for people with anxiety.

“Meditation, when done in this particular way as a daily practice, is very effective in treating anxiety, as effective as a drug,” says the study’s lead author, psychiatrist Elizabeth Hoge of Georgetown University.

Besides reducing anxiety, MBSR also had fewer problematic side effects than Lexapro: 79% of patients in the Lexapro group reported at least one side effect during the course of their treatment, while only 5% of the MBSR patients did (and that was limited to increased anxiety). Side effects in the Lexapro group, however, included other things, like poor sleep, nausea, jitteriness, sweating, headaches, delayed orgasms, and decreased libido. While 10% of the Lexapro group dropped out of treatment during the trial due to side effects, none dropped out of the MBSR treatment for that reason.

This suggests that MBSR may be a good alternative for those suffering from anxiety who don’t want to risk taking drugs.

“Side effects are common with many of the SSRI antidepressants [like Lexapro], and we don’t know exactly why,” says Hoge. “For some people, those side effects are tolerable; but for others, they’re totally unacceptable, and a meditation training may be a great option.”

Why does meditation have these effects on anxiety? Hoge believes that it’s because of the way anxious people’s minds work and how meditation counteracts that. She points to how people with anxiety are more likely to over-identify with their thoughts and feelings and become alarmed by them, leading to catastrophic thinking. Meditation helps people feel a bit more distant from their experiences without clinging to them, she says, helping people to cope better.

“All of the meditation practices involve paying attention to the present moment, but in a particular way—with openness and acceptance,” she says. “Whatever mental phenomenon arises spontaneously in the moment, you can accept it and let it pass.”

Another reason that meditation helps, she suspects, is that it trains people to be more self-compassionate. Many people with anxiety or depression are hard on themselves, which compounds their problems, and meditation may foster more self-kindness.

“There’s an implicit suggestion of self-compassion in meditation instructions, which tell you to pay attention to your thoughts, feelings, sensations, memories, or whatever without judging them,” she says. “That’s a great way for people to practice being open and accepting of themselves and their experiences—of being kind.”

Hoge’s study shows basically equivalent long-term outcomes for both MBSR and Lexapro, at least over the first six months. But she doesn’t think that proves much. It’s hard to know if people did other things to combat their anxiety after the intervention was over, and that will color the longitudinal results.

In addition, both drugs and MBSR can have declining effectiveness over time, as drugs may lose their potency and people doing MBSR may start slacking off on their daily practice. So, though both treatments seem to have some staying power, it’s hard to conclude that from her study alone.

Also, MBSR training can be somewhat cumbersome. It takes time, energy, and commitment to practice regularly—one of the reasons that the overall dropout rates in Hoge’s experiment were similar for MBSR and Lexapro. However, Hoge warns against assuming other quick-fix mindfulness programs—like online apps or shorter classes—will be as effective as Lexapro against severe anxiety. Apps don’t encourage people to devote enough time to meditation, she says, and there’s no human interaction component in the training—something she thinks makes a difference.

“I don’t want people to think meditation is just as easy as taking a drug—like, they’re going to do Calm or Headspace and get relief,” she says. “Those might be better than nothing—I don’t really know. But an in-person class is really the gold standard.”

Instead, she compares the benefits of meditation training to those of physical exercise—another behavioral intervention that requires perseverance, but provides a lot of relief from psychiatric symptoms without the use of medication.

“There’s great data now showing that aerobic exercise protects against depression and anxiety—almost as good as drug treatment,” she says. “It takes work to go running or do whatever exercise you do every day or nearly every day. But, for some, it’s worth it.”

Another problem? MBSR is not free, and insurers generally won’t cover it, says Hoge. This she would like to see change, and the results from her experiment may help move things in that direction. By adding to a growing body of research showing the mental health benefits of practicing mindfulness meditation—and providing evidence from a highly controlled, clinical trial—she hopes insurers will change their minds and start paying for MBSR.

Though she advocates for MBSR as a treatment option, Hoge recognizes that it may not be for everyone. But, given that patients in her study were randomly assigned to do MBSR without choosing it and it was still effective against their anxiety, one has to wonder how much better results might have been if people selected it as their treatment of choice.

For now, there’s not enough research to say one way or the other. But studies like this one are good news for anxiety sufferers.

“When people can come into a clinic and be seen by a psychologist or psychiatrist and given a full evaluation—where the [professional] can discuss with the patient the option of medication, psychotherapy, or meditation—that will be a good thing,” says Hoge.

— Jill Suttie, Psy.D., serves as a staff writer and contributing editor for Greater Good. Based at UC-Berkeley, Greater Good highlights ground breaking scientific research into the roots of compassion and altruism. Copyright Greater Good.

— Jill Suttie, Psy.D., serves as a staff writer and contributing editor for Greater Good. Based at UC-Berkeley, Greater Good highlights ground breaking scientific research into the roots of compassion and altruism. Copyright Greater Good.

The Study:

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Escitalopram for the Treatment of Adults With Anxiety Disorders: A Randomized Clinical Trial (JAMA Psychiatry). Key Points:

Question: Is mindfulness-based stress reduction noninferior to escitalopram for the treatment of anxiety disorders?

Findings: In this randomized clinical trial of 276 adults with anxiety disorders, 8‑week treatment with mindfulness-based stress reduction was noninferior to escitalopram.

Meaning: In this study, mindfulness-based stress reduction was a well-tolerated treatment option with comparable effectiveness to a first-line medication for patients with anxiety disorders.