Large neuroimaging study finds social isolation to be an early indicator of increased dementia risk

Why do we get a buzz from being in large groups at festivals, jubilees and other public events? According to the social brain hypothesis, it’s because the human brain specifically evolved to support social interactions. Studies have shown that belonging to a group can lead to improved wellbeing and increased satisfaction with life.

Why do we get a buzz from being in large groups at festivals, jubilees and other public events? According to the social brain hypothesis, it’s because the human brain specifically evolved to support social interactions. Studies have shown that belonging to a group can lead to improved wellbeing and increased satisfaction with life.

Unfortunately though, many people are lonely or socially isolated.

And if the human brain really did evolve for social interaction, we should expect this to affect it significantly. Our recent study, published in Neurology, shows that social isolation is linked to changes in brain structure and cognition – the mental process of acquiring knowledge – it even carries an increased risk of dementia in older adults.

There’s already a lot of evidence in support of the social brain hypothesis. One study mapped the brain regions associated with social interaction in approximately 7,000 people. It showed that brain regions consistently involved in diverse social interactions are strongly linked to networks that support cognition, including the default mode network (which is active when we are not focusing on the outside world), the salience network (which helps us select what we pay attention to), the subcortical network (involved in memory, emotion and motivation) and the central executive network (which enables us to regulate our emotions).

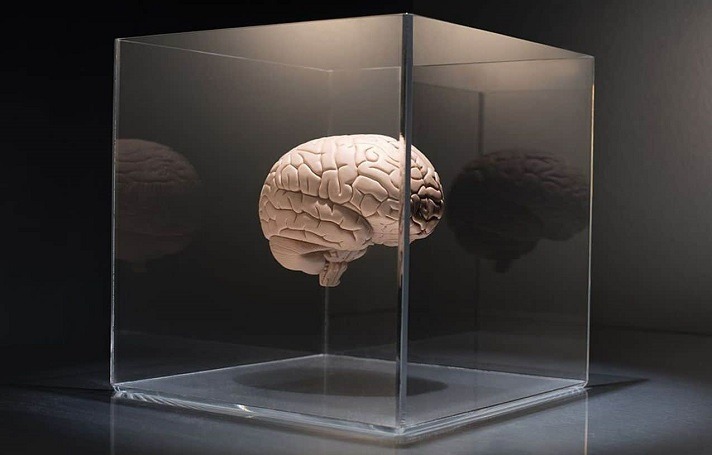

We wanted to look more closely at how social isolation affects grey matter – brain regions in the outer layer of the brain, consisting of neurons. We, therefore, investigated data from nearly 500,000 people from the UK Biobank, with a mean age of 57. People were classified as socially isolated if they were living alone, had social contact less than monthly and participated in social activities less than weekly.

Our study also included neuroimaging (MRI) data from approximately 32,000 people. This showed that socially isolated people had poorer cognition, including in memory and reaction time, and lower volume of grey matter in many parts of the brain. These areas included the temporal region (which processes sounds and helps encode memory), the frontal lobe (which is involved in attention, planning and complex cognitive tasks) and the hippocampus – a key area involved in learning and memory, which is typically disrupted early in Alzheimer’s disease.

We also found a link between the lower grey matter volumes and specific genetic processes that are involved in Alzheimer’s disease.

There were follow-ups with participants 12 years later. This showed that those who were socially isolated, but not lonely, had a 26% increased risk of dementia.

Context and brain mechanisms:

Social isolation needs to be examined in more detail in future studies to determine the exact mechanisms behind its profound effects on our brains. But it is clear that, if you are isolated, you may be suffering from chronic stress. This in turn has a major impact on your brain, and also on your physical health.

Another factor may be that if we don’t use certain brain areas, we lose some of their function. A study with taxi drivers showed that the more they memorised routes and addresses, the more the volume of the hippocampus increased. It is possible that if we don’t regularly engage in social discussion, for example, our use of language and other cognitive processes, such as attention and memory, will diminish.

This may affect our ability to do many complex cognitive tasks – memory and attention are crucial to complex cognitive thinking in general.

Building cognitive reserve via social interaction:

We know that a strong set of thinking abilities throughout life, called “cognitive reserve”, can be built up through keeping your brain active. A good way to do this is by learning new things, such as another language or a musical instrument. Cognitive reserve has been shown to ameliorate the course and severity of ageing. For example, it can protect against a number of illnesses or mental health disorders, including forms of dementia, schizophrenia and depression, especially following traumatic brain injury.

There are also lifestyle elements that can improve your cognition and wellbeing, which include a healthy diet and exercise. For Alzheimer’s disease, there are a few pharmacological treatments, but the efficacy of these need to be improved and side effects need to be reduced. There is hope that in the future there will be better treatments for ageing and dementia. One avenue of inquiry in this regard is exogenous ketones — an alternative energy source to glucose – which can be ingested via nutritional supplements.

But as our study shows, tackling social isolation could also help, particularly in old age. Health authorities should do more to check on who is isolated and arrange social activities to help them.

When people are not in a position to interact in person, technology may provide a substitute. However, this may be more applicable to younger generations who are familiar with using technology to communicate. But with training, it may also be effective in reducing social isolation in older adults.

Social interaction is hugely important. One study found that the size of our social group is actually associated with the volume of the orbitofrontal cortex (involved in social cognition and emotion).

But how many friends do we need? Researchers often refer to “Dunbar’s number” to describe the size of social groups, finding that we are not able to maintain more than 150 relationships and only typically manage five close relationships. However, there are some reports which suggest a lack of empirical evidence surrounding Dunbar’s number and further research into the optimal size of social groups is required.

It is hard to argue with the fact that humans are social animals and gain enjoyment from connecting with others, whatever age we are. But, as we are increasingly uncovering, it also crucial for the health of our cognition.

– Barbara Jacquelyn Sahakian is a Professor of Clinical Neuropsychology at University of Cambridge. Christelle Langley is a Postdoc Research Associate at University of Cambridge. Chun Shen is a Postdoc research fellow at Fudan University. Jianfeng Feng is a Professor of Science and Technology for Brain-Inspired Intelligence at Fudan University. This article was originally published on The Conversation.