From “Eminence-based” to Evidence-based mental healthcare: Time to focus on quality and accountability

For the mental health crisis of care, quality is as much of a problem as quantity.

For the mental health crisis of care, quality is as much of a problem as quantity.

Most people who seek mental health care for the first time are baffled by how to find a clinician. I know what many parents felt. When my daughter, Lara, finished her first semester at Oberlin, she returned home to Atlanta thin and exhausted. I was excited to have her back home and entirely clueless about her desperate struggle with anorexia. In fact, as I learned later, she had been driven by obsessions about her weight and her appearance for over a year by that point. As was true of Amy, her perfectionism and her shame at not being perfect kept her from sharing this struggle. And now, in a crisis after a year of anguish, she was asking for help. As a professor of psychiatry at the university, I should have noticed her serious mental illness, and yet I missed it. At least, now that Lara was asking for help, I should know where to find the best care. But the university had no resources specifically for eating disorders, and I could not find a center for her treatment any better than Amy’s parents had. Fortunately, Lara, ever the problem solver, found an intensive outpatient program with a superb therapist and began a long, successful road to recovery. But even as a professional in this space, I found it difficult to navigate the maze of care. The first issue is that there are so many different types of professionals: social workers, marriage and family counselors, clinical psychologists, professional psychologists, psychiatrists —and they all call themselves therapists. The choice really matters, because what you receive depends largely on whom you see.

This is not true for cancer or asthma or heart disease, but in mental health care, there is little consensus among the various care providers as to how to approach even the most common forms of mental illness.

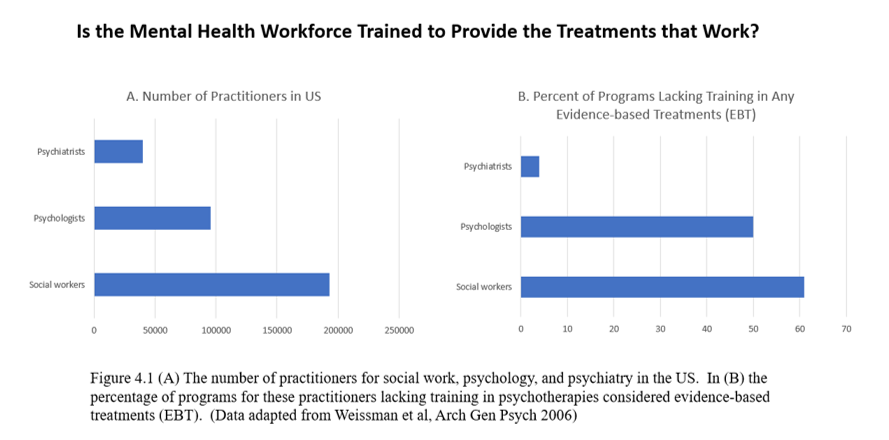

Although I frequently hear that we don’t have enough mental health providers, the numbers don’t reveal a shortage. We have nearly 700,000 mental health providers in the United States, more than half being in the traditional psychotherapy professions of social worker, marriage and family therapist, or licensed counselor. The number of mental health therapists is considerably greater than, for instance, the 209,000 physical therapists or the 200,000 dental hygienists in the U.S. Psychiatrists are only about 5 percent of the total workforce, and child psychiatrists are roughly 1 percent. These numbers might seem paltry, but there are more psychiatrists than any other specialists in medicine (outside of internal medicine and pediatrics). And the relative number of psychiatrists in the U.S. is far higher than in most of the world. Although 45 percent of the world’s population lives in countries with fewer than one psychiatrist per 100,000 people, in the U.S. the number exceeds twelve psychiatrists per 100,000.

So why is it so difficult to get an appointment to see a clinician? In absolute numbers, the U.S. mental health workforce reaches nearly two professionals per thousand. In fact, with 14.2 million adults with serious mental illness, we theoretically have roughly one therapist for every twenty people in need.

So, what’s the problem? The uneven distribution of the workforce is part of the problem. The geographic disparity in mental health services within the U.S. is almost as severe as the disparity globally. The number of psychiatrists varies from 5.2 per 100,000 people in Idaho to 24.7 per 100,000 in Massachusetts. While there are nearly threefold more psychologists than psychiatrists in the U.S., they are even more unevenly distributed: 7.9 per 100,000 people in Mississippi versus 76.0 per 100,000 in Massachusetts. Even clinical social workers, who make up the largest sector of the mental health workforce, show this kind of geographic distribution, from 22.0 per 100,000 in Montana to 186.6 per 100,000 in Maine.

For any of us seeking quality care, there are three major barriers beyond the issues of access. First, the available therapy workforce often has not been trained in the treatments that work. Second, the care is highly fragmented. Different forms of mental health care are given by different providers, with mental health and substance abuse care rarely coordinated and behavioral health segregated from the rest of health care. Finally, there is little accountability because mental health providers rarely measure outcomes. You can’t improve quality without measurement.

The real challenge is not finding a therapist, it’s finding a therapist who knows how to provide the treatments that work. In the early 2000s, Myrna Weissman was trying to understand why so few therapists use scientifically based treatments. She found that over 60 percent of professional schools of psychology and master’s level social work programs did not include any supervised training for any scientifically based therapy.

– Data included in the downloadable PDF that accompanies the book Healing; available via www.thomasinselmd.com

If these mental health professionals are not trained to provide treatments that are scientifically proven, what are they trained to do? Few programs require supervised training in any form of therapy, but most expose students to psychodynamic psychotherapy, which explores early conflicts.

In contrast to evidence-based care, I call this “eminence-based care.”

In contrast to evidence-based care, I call this “eminence-based care.”

– This is an adapted excerpt from the new book Healing: Our Path from Mental Illness to Mental Health by Thomas lnsel, MD, a psychiatrist, neuroscientist and national leader in mental health research, policy, and technology. He was the founding Director of the Center for Behavioral Neuroscience at Emory University, led the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) for 13 years, advanced digital phenotyping at Google X, and co-founded Mindstrong Health and Humanest Care among others. More information at www.thomasinselmd.com.