Rationality doesn’t equal efficiency: Cellphone data shows how we navigate cities

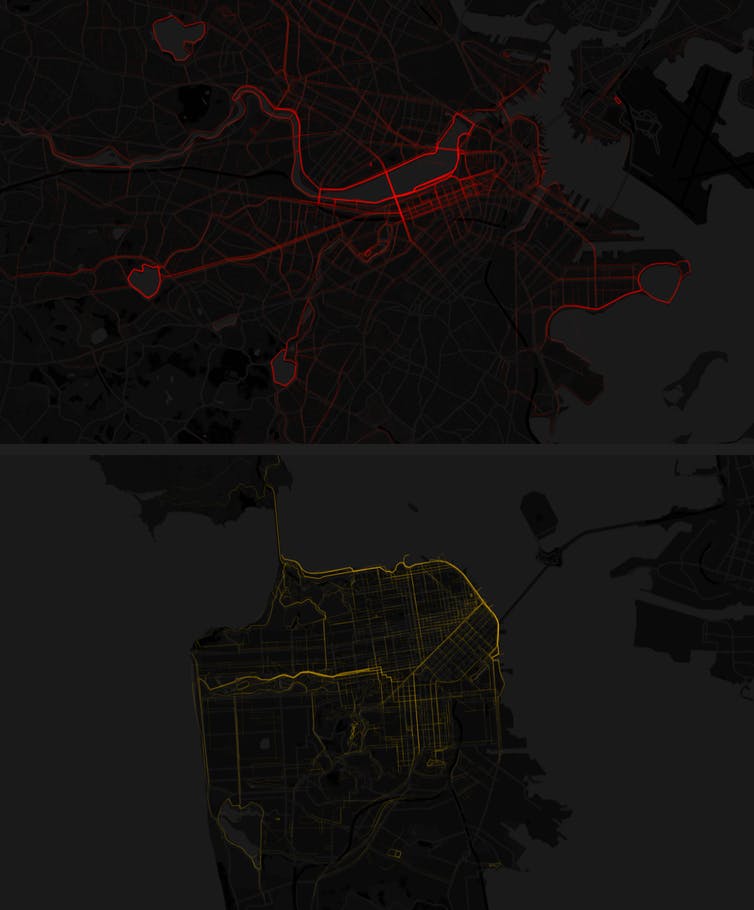

The paths people take are recorded by their cellphones. Anonymous data from thousands of phones shows the paths people take in Boston (above) and San Francisco (below). Carlo Ratti, CC BY-ND

Think of your morning walk to work, school or your favorite coffee shop. Are you taking the shortest possible route to your destination? According to big data research that my colleagues and I conducted, the answer is no: People’s brains are not wired for optimal navigation.

Instead of calculating the shortest path, people try to point straight toward their destinations – we call it the “pointiest path” – even if it is not the most efficient way to walk.

As a researcher who studies urban environments and human behavior, I have always been interested in how people experience cities, and how studying this can tell researchers something about human nature and how we’ve evolved.

Chasing down a hunch

Long before I could run an experiment, I had a hunch. Twenty years ago, I was a student at the University of Cambridge, and I realized that the path I followed between my bedroom at Darwin College and my department on Chaucer Road was, in fact, two different paths. On the way to Chaucer, I would take one set of turns. On the way back home, another.

Surely one route was more efficient than the other, but I had drifted into adapting two, one for each direction. I was consistently inconsistent, a small but frustrating realization for a student devoting his life to rational thinking. Was it just me or were my fellow classmates – and my fellow humans – doing the same?

Around 10 years ago, I found tools that could help answer my question. At the Senseable City Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, we were pioneering the science of understanding cities by analyzing big data, and in particular digital traces from cellphones. Studying human mobility, we noticed that, on the whole, people’s routes were not conservative, meaning they did not preserve the same path from A to B as the opposite direction, from B to A.

However, the technology and analytical methods of that time prevented us from learning more – in 2011, we could not reliably tell a pedestrian apart from a car. We were close, but still a few technological steps short of tackling the enigma of human navigation in cities.

Big cities, big data

Today, thanks to access to data sets of unparalleled size and accuracy, we can go further. Every day, everyone’s smartphones and apps collect thousands of data points. Collaborating with colleagues at the MIT Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and other international scholars, we analyzed a massive database of anonymized pedestrian movement patterns in San Francisco and Boston. Our results consider questions that my young self at Cambridge didn’t know to ask.

After we analyzed pedestrian movement, it became clear that I am not the only one who navigates this way: Human beings are not optimal navigators. After accounting for possible interference from people letting Google Maps choose their path for them, our analysis of our big data sets fueled several interconnected discoveries.

First, human beings consistently deviate from the shortest possible path, and our deviations increase over longer distances. This finding probably seems intuitive. Previous research has already shown how people rely on landmarks and miscalculate the lengths of streets.

Our study was able to go a step further: developing a model with the capability to accurately predict the slightly irrational paths that we found in our data. We discovered that the most predictive model – representing the most common mode of city navigation – was not the quickest path, but instead one that tried to minimize the angle between the direction a person is moving and the line from the person to their destination.

This finding appears to be consistent across different cities. We found evidence of walkers attempting to minimize this angle in both the famously convoluted streets of Boston and the orderly grid of San Francisco. Scientists have recorded similar behaviors in animals, which are described in the research literature as vector-based navigation. Perhaps the entire animal kingdom shares the idiosyncratic tendencies that confused me on my walk to work.

Evolution: From savannas to smartphones

Why might everyone travel this way? It’s possible that the desire to point in the right direction is a legacy of evolution. In the savanna, calculating the shortest route and pointing straight at the target would have led to very similar outcomes. It is only today that the strictures of urban life – traffic, crowds and looping streets – have made it more obvious that people’s shorthand is not quite optimal.

Still, vector-based navigation may have its charms. Evolution is a story of trade-offs, not optimizations, and the cognitive load of calculating a perfect path rather than relying on the simpler pointing method might not be worth a few saved minutes. After all, early humans had to preserve brain power for dodging stampeding elephants, just like people today might need to focus on avoiding aggressive SUVs. This imperfect system has been good enough for untold generations.

However, people are no longer walking, or even thinking, alone. They are increasingly wedded to digital technologies, to the point that phones represent extensions of their bodies. Some have argued that humans are becoming cyborgs.

This experiment reminds us of the catch: Technological prostheses do not think like their creators. Computers are perfectly rational. They do exactly what code tells them to do. Brains, on the other hand, achieve a “bounded rationality” of “good enoughs” and necessary compromises. As these two distinct entities become increasingly entangled and collide – on Google Maps, Facebook or a self-driving car – it’s important to remember how they are different from each other.

Looking back on my university days, it is a sobering thought that humanity’s biological source code remains much more similar to that of a rat in the street than that of the computers in our pockets. The more people become wedded to technology, the more important it becomes to make technologies that accommodate human irrationalities and idiosyncrasies.

– An architect and engineer by training, Professor Carlo Ratti teaches at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he directs the Senseable City Lab. This article was originally published on The Conversation.

– An architect and engineer by training, Professor Carlo Ratti teaches at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he directs the Senseable City Lab. This article was originally published on The Conversation.