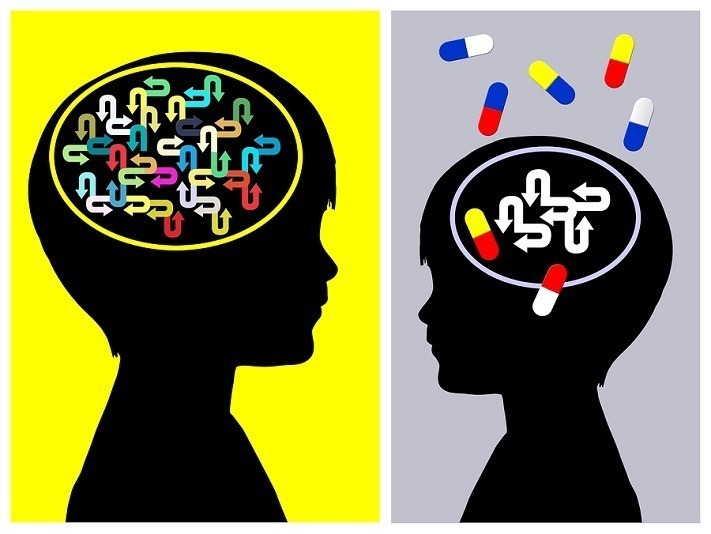

What should come first to treat ADHD in children, behavior therapy or stimulant medication?

Stimulant medication treatment and behavior therapy are currently the two child ADHD treatments with the strongest research support. However, when parents begin treatment for their child, or when professionals are initiating treatment with a new client, there is no research to guide the decision of which approach to begin with.

Stimulant medication treatment and behavior therapy are currently the two child ADHD treatments with the strongest research support. However, when parents begin treatment for their child, or when professionals are initiating treatment with a new client, there is no research to guide the decision of which approach to begin with.

Is it better to start with medication treatment and add behavior therapy if needed? Or, should behavior therapy come first with medication added if the child’s response is not sufficient? Or, is it always preferable to begin with combined treatment? Does the order in which treatment begins even make a difference? Different professional organizations have published different recommendations on this issue but none are based on research that has directly examined these fundamental questions.

A study published in the Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, Treatment sequencing for childhood ADHD: A multiple-randomization study of medication and behavioral interventions, helps establish whether ADHD treatment outcomes differ depending on whether medication or behavior therapy is tried first.

The Study:

Participants were 152 children with ADHD ages 5 to 12. Children were randomly assigned to begin treatment with either a relatively low dose of stimulant medication or with low intensity behavior therapy.

A low dose of medication was selected — most children received 10 mg per day of an extended release stimulant — to be consistent with how such treatment is typically delivered in community settings, e.g., start low, see how the child responds, and adjust upwards if needed. Behavior therapy consisted on an 8‑week group parent training program to help parents manage their child’s behavior more effectively; children themselves received concurrent social skills training to promote better peer relations.

As part of the parent training program, parents learned how to implement a Daily Report Card (DRC) program that provided daily feedback from their child’s teacher about his/ her success in meeting important goals each day.

After 8 weeks, the child’s functioning at school and home was reevaluated on a monthly basis. If parent and teacher report indicated the child was doing well, the child simply continued on the initial treatment. Children who were doing well on meds continued on their same dose. For children in the behavior therapy group, parents continued to implement what they had learned and were offered monthly booster sessions.

For children whose ADHD symptoms and behaviors were not adequately managed, treatment changes were initiated. Those who started on meds had either their medication treatment enhanced, e.g., higher dose, a second dose after school, or the behavior therapy program added to their medication treatment. For children who started with behavior therapy, either low dose medication was added or their behavioral treatment was intensified. Which treatment was added was also determined at random rather than by parents’ choice.

By the end of the 12-month study, there were thus 6 groups of children: 1) Those who started on meds and whose treatment did not change; 2) Those who started on meds and moved to more individualized medication treatment; 3) Those who started on meds but later began behavior therapy; 4) Those who started with behavior therapy and were maintained on this initial treatment; 5) Those who started with behavior therapy but moved to more intensive, individualized behavior therapy; and 6) Those who started with behavior therapy and who later began taking medication.

Outcome measures:

The primary outcome measure was an observation of children’s classroom behavior made by trained observers. These observers visited the classroom every 4 to 6 weeks and conducted 40 minute observations of children’s behavior during academic tasks. During each observation, they noted all instances of rule-breaking behavior, e.g., noncompliance with teacher requests, disrupting others, leaving seat without permission, etc. In the analysis reported below, the final observation during the school year was used as the primary outcome.

A number of other measures were also collected including the number of times each child was removed from the classroom for disciplinary reasons, as well as parent and teacher behavior ratings.

Based on the above design, three primary research questions were addressed.

- Does initiating ADHD treatment with low doses of medication or behavioral therapy produce better child outcomes at the end of the school year in terms of their classroom behavior?

- If a child is started on medication treatment, and the initial regimen is not adequate, is it better to adjust medication treatment or stick with the initial medication regime and add behavioral therapy?

- If a child is started on behavioral therapy and the treatment response is not sufficient, is it better to add low dose medication or intensify the behavioral treatment.

Results:

A complex study like this reports many results; what is summarized below are what I feel are the most important overall findings.

1. On average, children who started on behavioral therapy were doing better at the end of the school year than children who started with medication. Those who started with behavior therapy had an average of 8.4 classroom rule violations per hour compared to 12.6 rules violations per hour for children started on medication. They also tended to experience fewer removals from class for disciplinary violations, 1.6 vs. 3.1. Group differences for parent and teacher ratings were not significant.

2. For children who began on medication treatment and who did not respond sufficiently, enhancing medication treatment was substantially more helpful than adding behavior therapy. Compared to adding behavior therapy, adapting the medication treatment resulted in significantly fewer classroom rule violations and out-of-class disciplinary events. In fact, the group for whom behavior therapy was added to medication had the worst outcomes of all. This may have been because when medication was started first, parents were highly unlikely to engage in behavior therapy when it was added. Thus, these children essentially remained on a single treatment that was not sufficient, as their medication was not adjusted in the study.

3. For children who began with behavior therapy and responded insufficiently, there was not clear advantage to intensifying the behavior therapy or adding low dose stimulant medication — both yielded benefits that varied across the different outcome measures.

Summary and implications:

These results have direct relevance for clinical practice as the treatments employed were not high-powered versions of medication and behavior therapy that are difficult to obtain outside a research context. Instead, the relatively low-dose treatment strategies are ones that can be implemented in schools, primary care, and community mental health settings.

The authors argue that their findings raise serious questions about the common approach to beginning ADHD treatment with medication alone. They suggest that beginning with a low-intensity behavioral treatment is preferred because it was associated with better end of school year outcomes. When behavior therapy is not sufficient, either intensifying this approach or adding low dose stimulant medication is likely to produced improved child outcomes.

In contrast, if treatment begins with medication and is insufficient, adding behavior therapy is not effective because parents are unlikely to follow through on the physician’s recommendation. This may result in intensifying medication treatment as the only viable option. Children treated this way are likely to be maintained on higher doses of medication than would be necessary if behavioral treatment was started first, thus increasing the risk of adverse side affects and the premature termination of treatment.

Because of this, the authors suggest that children with ADHD should receive a stepwise approach to treatment, beginning with low intensity behavior therapy and increasing intensity or adding low dose medication only if necessary. They conclude that this would be a cost-effective public health approach for treating childhood ADHD.

This is an impressive study with important findings. As with any study, however, the findings would be important to replicate and there are limitations that need to be considered. For me, the largest concern is that despite efforts to provide treatments similar to how they are offered in community settings, the extent to which these findings can be generalized to real world settings is uncertain. There are several reasons for this.

First, in this study children’s ongoing response to treatment was systematically monitored on a monthly basis so that additional treatment could be implemented if indicated. Research has shown, however, that such systematic monitoring is rarely done in primary care settings.

Second, there are many families who begin their child on a combination of medication treatment and behavior therapy, as multimodal treatment is often recommended as the preferred approach. In this study, however, this was never done. As a result, we don’t learn whether beginning with combined medication and behavioral treatment may be superior to starting with either in isolation.

Third, parents did not choose which treatment their child started with, or how treatment was augmented if their child’s response was not sufficient. Instead, random assignment was used to determine what treatment(s) children received.

While this randomization is an essential part of a controlled study, in community settings, parents decide what initial and subsequent treatment their child receives. Thus, finding that parents were unlikely to engage in behavior therapy when it followed an insufficient response to medication may not reflect what happens when parents themselves decide to include behavior therapy. It does highlight, however, that physicians need to be very careful about assuming parents will follow through on referrals to behavioral therapy they may make.

Finally, I was surprised that no assessments of children’s academic work and school performance were included. Instead, all outcome measures were focused on behavior.

The authors note several of the above limitations themselves and will no doubt try to address them in subsequent work. These limitations not withstanding, this is an impressive and clinically relevant study that may contribute to an important reconsideration of how children with ADHD are typically treated.

– Dr. David Rabiner is a child clinical psychologist and Director of Undergraduate Studies in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at Duke University. He publishes the Attention Research Update, an online newsletter that helps parents, professionals, and educators keep up with the latest research on ADHD.

The Study in Context:

- A brief sleep intervention can bring measurable and sustained benefits to children with ADHD

- Study finds combined pharma + non-pharma treatment most beneficial to help youth with ADHD address long-term academic difficulties

- Having ADHD costs $1.1 million in lower lifetime earnings, even when “treated”

- What are cognitive abilities and how to boost them?