The frontal lobes, the little brain down under and “Stayin’ Alive” (3/3)

__

__

[Editor’s note: Continued from Exploring the human brain and how it responds to stress (1/3) and On World Health Day 2020, let’s discuss the stress response and the General Adaptation Syndrome (2/3)]

More on the Cortex, the Limbic System, and Stress:

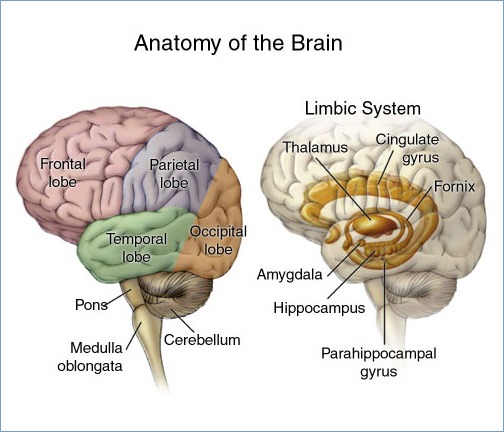

The cortex is made up of four major sections, arranged from the front to the back. These are called the frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes. Each of the four lobes is found in both hemispheres, and each is responsible for different, specialized cognitive functions. For example, the occipital lobe contains the primary visual cortex, and the temporal lobe (located by the temples, and close to the ears) contains the primary auditory cortex.

The frontal lobes are positioned at the front most region of the cerebral cortex and are involved in movement, decision making, problem solving, and planning. There are three main divisions of the frontal lobes. They are the prefrontal cortex, the premotor area, and the motor area. The frontal lobe of the human brain contains areas devoted to abilities that are enhanced in or unique to humans. The prefrontal cortex is responsible for planning complex cognitive behaviors, the expression of personality, decision making, and social behavior, as well as the orchestration of thoughts and actions necessary for a person to carry out goals. A specialized area known as the ventrolateral pre-frontal cortex has primary responsibility for the processing of complex language. It is more commonly called Broca’s area, named for a nineteenth-century French physician who determined its role.

In humans and other primates, an area located at the forward part of the prefrontal cortex is called the orbitofrontal cortex. It gets its name from its position immediately above the orbits, the sockets in which the eyes are located. The orbitofrontal cortex is very involved in interpreting rewards, decision making, and processing social and emotional information. For this reason, some consider it to be a part of the limbic system.

The amygdala, a part of the limbic system, is a brain structure that is responsible for decoding emotions, especially those the brain perceives as threats. As we evolved as a species, many of our alarm circuits have been grouped together in the amygdala. Not surprisingly, many regions of the brain send neurons into the amygdala. As a result, lots of sensory messages travel instantaneously to the amygdala to inform it of potential dangers lurking in our neighborhood. The amygdala is our guard dog.

The amygdala is directly wired to the hippocampus, also a part of the limbic system. Since the hippocampus is involved in storing and retrieving explicit memories, it feeds the amygdala with strong emotions triggered by these recollections. Why is this important? If a child has a negative experience in school, like being terribly embarrassed when asked to read in front of the class, the hippocampus just won’t let go of this memory, and it shouts it out to the amygdala. Since the amygdala has signed a no confidentiality agreement, it sends a warning to the rest of the brain to go into protection mode. A rather amazing arrangement, don’t you think?

What’s really interesting about this is that the hippocampus specializes in processing the context of a situation. As a result, the child (or adult) under stress generalizes the entire situation and uses it as justification for anxiety or stress: “Hey, they’re telling me to go to social studies class.” Even though not everything about social studies may be a threat — perhaps just the fact that they read out loud in there — the hippocampus sends out a general alert. So the student responds by protesting the whole enchilada: “No way I’m going there.”

The amygdala is also wired to the medial prefrontal cortex. Want to know why this is important? This is the area of the brain that seems to be involved in planning a specific response to a threat to safety.

Here’s how it works: the child is hit with the gigantic Titanic news (which may be just “social studies coming up next” to the rest of the group, but it’s “Submerged iceberg ahead!” to the student worried about perceived horrors there). This two-way communication between the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system (particularly the amygdala) enables us to exercise conscious control over our anxiety. The emotion — cognition connection allows us to feel that we can do something about the danger that lies ahead. The child is then faced with the necessity of choosing a course of action that looks best for getting out of danger. This seems very protective but tends to be counterproductive, because the very mechanism that allows us to create an escape plan can actually create anxiety.

The brain not only allows us to imagine a negative outcome, which can help us avoid danger, it makes it possible for us to imagine dangers that do not actually exist.

The Thalamus Bone:

Of course, it’s not really a bone; it’s a plum — shaped mass of gray matter that’s multilayered and multifaceted. The thalamus, another part of the limbic system, sits on top of the hypothalamus which, in turn, sits on top of the brain stem, which is in the center of the base of the brain. This is a great location for the thalamus because it acts as a relay system that sends nerve fibers upstairs to all parts of the cerebral cortex as well as many sub-cortical (underneath the cortex) parts of the brain. The thalamus receives information from every sensory organ and its associated neurons except the olfactory (smell) system. The hypothalamus gets information from the eyes, the ears, the skin, and the tongue, and it forwards these messages to the corresponding areas of the cortex where they are processed. In terms of stress, this relay system is how the brain knows that it’s in a dangerous environment.

The Little Brain Down Under:

Sitting under the occipital and temporal lobes of the brain is the cerebellum. It’s about the size of a child’s fist. Because it looks like a separate brainlike structure attached to the underside of the cortex, the cerebellum is sometimes referred to as the “little brain.” It’s connected to the brain stem, which in turn connects the brain to the spinal cord. The cerebellum used to be relegated to the very simple role of helping us maintain balance when we walk or run, but modern neuroscience has found that the cerebellum plays a much larger and more important role than that.

Like the hypothalamus, it is involved in cognitive functions, including attention and language, as well as the ability to hold mental images in the “mind’s eye.” This part of the brain is important to the discussion of stress, since recent research has shown that the cerebellum also plays a key role in regulating responses to pleasure and to fear — strong forces when it comes to loving what’s next in our schedule or hating it.

The Bee Gees song “Stayin’ Alive” reached #1 on the pop charts in 1977. Maybe it was the beat, maybe it was John Travolta’s dancing. Or maybe it’s that the Gibb brothers’ central lyric is quite literally always playing in our head. Keeping us safe —that is, “stayin’ alive ”— is the primary mission of the brain. The brain works very fast and very hard —mostly in the background— to do just that. It’s exquisitely positioned close to ears, eyes, nose, and mouth so the signals from those sensory organs get into it without delay. Everything we encounter in our daily lives gets sent, incredibly fast, from our ears, nose, mouth, skin, and eyes to our brain for processing. The brain controls the other organ systems of the body, either by activating muscles or by causing secretion of chemicals such as hormones. That three-pound mass of gray and white matter somewhat miraculously uses this unending and potentially overwhelming stream of information to change our physical position, our pattern of thought, and our feelings or emotions — all in the service of keeping us alive. After all, a brain without a body is, if you will forgive me, nobody at all.

Now that you have had an introduction to this marvelous and complex organ called the brain, it hope it will easier to understand what happens to the brain under stress, and how to cope with it.

– Dr. Jerome (Jerry) Schultz is a Clinical Neuropsychologist, author and speaker who has provided clinical services, consultation and staff development to hundreds of private and public schools in the US and abroad during his 35-year career. This is an adapted excerpt from his latest book Nowhere to Hide: Why Kids with ADHD & LD Hate School and What We Can Do About It, which examines the role of stress in learning.

– Dr. Jerome (Jerry) Schultz is a Clinical Neuropsychologist, author and speaker who has provided clinical services, consultation and staff development to hundreds of private and public schools in the US and abroad during his 35-year career. This is an adapted excerpt from his latest book Nowhere to Hide: Why Kids with ADHD & LD Hate School and What We Can Do About It, which examines the role of stress in learning.

Resources to regulate stress:

Four tips to practice good mental hygiene during the coronavirus outbreak

Study finds a key ingredient in mindfulness training: Acceptance (not acquiescence)

Positive solitude, Feeling active and Future-mindednes: Three Keys to Well-being

New study reinforces the importance of walking through forests for mental and general health

Six tips to build resilience and prevent brain-damaging stress