On World Health Day 2020, let’s discuss the stress response and the General Adaptation Syndrome (2/3)

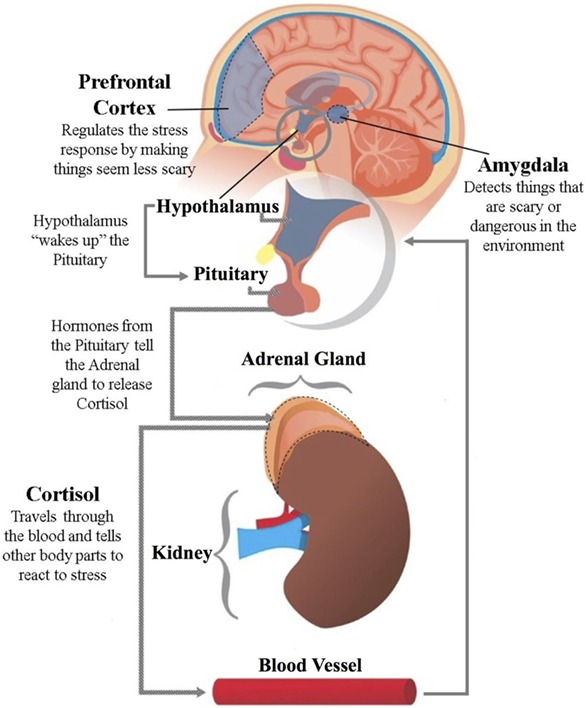

The hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis acts to release cortisol into the blood stream, as cortisol calls the body into action to combat stress. When high amounts of cortisol interact with the hypothalamus, the HPA axis will slow down its activity. The amygdala detects stress, while the prefrontal cortex regulates our reactions to stress. Source: Bezdek K and Telzer E (2017) Have No Fear, the Brain is Here! How Your Brain Responds to Stress. Front. Young Minds. 5:71. doi: 10.3389/frym.2017.00071

_______

[Editor’s note: Continued from yesterday’s Exploring the human brain and how it responds to stress (1/3)]

Stress was put on the map, so to speak, by a Hungarian — born Canadian endocrinologist named Hans Hugo Bruno Selye (ZEL — yeh) in 1950, when he presented his research on rats at the annual convention of the American Psychological Association. To explain the impact of stress, Selye proposed something he called the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS), which he said had three components. According to Selye, when an organism experiences some novel or threatening stimulus it responds with an alarm reaction. This is followed by what Selye referred to as the recovery or resistance stage, a period of time during which the brain repairs itself and stores the energy it will need to deal with the next stressful event.

He said that if the stress-causing events continue, neurological exhaustion can set in. This phenomenon came to be referred to popularly as burnout. It’s a state of mind characterized by a loss of motivation or drive and a feeling that you are no longer effective in your work. When this mental exhaustion sets in, a person feels emotionally flat, becomes cynical, and may display a lack of responsiveness to the needs of others.

What’s going on behind the scenes to cause this exhaustion? When humans are confronted by physical or mental stress or injury, an incredibly complex and critically important phenomenon rapidly takes place. First to be put on alert is the hypothalamus, which is situated deep inside the brain, under the thalamus and just above the brain stem. It’s only about the size of an almond, but plays a crucial role in linking the nervous system to the endocrine system. The hypothalamus is particularly interesting because it controls the production of hormones that affect how the body deals with stress. When danger looms, the hypothalamus sends a nearly instantaneous chemical message down the spinal cord to the adrenal glands, which are located just above the kidneys. This first message signals the production of a stress hormone called adrenaline, also called epinephrine, which is released into the blood stream. Norepinephrine also plays a role here. The interaction of these two hormones controls the amount of glucose (sugar) in the blood, speeds up the heart rate, and increases metabolism and blood pressure, all of which get the body ready to respond to the stressor.

Meanwhile, the hypothalamus has been closely monitoring these changes, as well as the source of the stress, and now releases something called a corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH). CRH travels along the neurons that go from the hypothalamus into the pituitary gland. This important gland, which is located at the base of the brain just above the roof of the mouth, releases something called adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into the bloodstream. ACTH travels down to the adrenal glands. This triggers the adrenal glands to release another hormone called cortisol. (Seriously, folks, isn’t this just amazing? )

Some cortisol is present in the bloodstream all the time. Normally, it’s present at higher levels in the morning and much lower at night. Incidentally, recent research has found that the opposite is true in some children with autism, a finding that might shed light on this condition. A little cortisol is a good thing. It can give you that quick burst of energy that comes in handy for survival purposes. For a brief period, it can enhance your memory and help boost your immune system. The right amount of cortisol helps keep your body systems in a healthy balance, and it can fight against inflammation and even lower your sensitivity to pain — all good things when you’ve been injured or if you’re going into battle against a single stressful opponent. But as often happens, too much of a good thing is, well … you know.

The stress response described here temporarily turns down or modifies nonessential bodily functions and activates the ones we need to keep us safe and healthy. It’s a wonderfully efficient system, and it’s fine-tuned to do its job well. Our brains and bodies are exquisitely designed to handle occasional acute stresses or injuries. However, they’re not well-equipped to handle ongoing or chronic stress.

Hans Selye’s research on the impact of stress in rats formed the foundation on which most subsequent studies about stress were built. Over time, and with the aid of sophisticated brain imagining technology, Selye’s hypothesis has been scrutinized and expanded. He believed that all types of stress resulted in the same reaction in the brain, but we now know that this process is much more complex. For example, contemporary research shows that the brain responds in different ways based on its perceptions of the degree of control that a person has over a stressful event. Here’s how this plays out in the brain.

The more stress people are under, or feel they are under, the greater the amount of cortisol that’s pumped into the blood by the adrenal glands. If too much cortisol is produced (as in acute stress) or is maintained at high levels in the bloodstream for too long (as in chronic stress), it can be very harmful. This hormone can cause a variety of physical problems, including blood sugar imbalances like hypoglycemia (a disturbance in the functioning of the thyroid), a decrease in muscle tissue and bone density, and high blood pressure. It can make the body susceptible to disease by lowering immunity and inflammatory responses in the body and making it harder for wounds to heal. Prolonged exposure to excessive amounts of cortisol has been implicated in the rise of obesity because too much cortisol has been shown to be related to an increase in the amount of abdominal fat.

The Human Brain Likes to Be in Balance

Fortunately, the brain has some built—in safety systems. Too much cortisol in the blood signals the brain and adrenal glands to decrease cortisol production. And under normal conditions, when the stress is overcome or brought under control (by fighting, fleeing, or turning into an immobile statue, or by mastering the threat), the hypothalamus starts sending out the orders to stand down. Stop producing cortisol! Event over! Under continuous stress, however, this feedback system breaks down. The hypothalamus keeps reading the stress as a threat, furtively sending messages to the pituitary gland, which screams out to the adrenal glands to keep pumping out cortisol, which at this point begins to be neurotoxic — poison to the brain.

Bruce Perry and Ronnie Pollard, a well-respected psychiatrist-neurologist team, have contributed much to our understanding of the impact of stress and how it affects this sense of balance, or homeostasis, in the brain. Sometimes when stress is so intense, the delicate interaction among the brain systems designed to handle it are thrown off balance. Other researchers have also shown that intense, acute, or traumatic stress presents such a shock to the brain and the stress response system that it actually reorganizes the way the brain responds to stress. For example, neuroendocrinologist Bruce McEwen and neuroscientist Frances Champagne have shown that repeated activation of the stress response can result in physical changes, caused by too many inflammatory proteins being pumped into the bloodstream.

Let me explain it this way: It’s rather like the keys of a piano being hit so hard that the impact puts the strings out of tune. The piano still plays, but it plays differently. While another hard hit on the keys might have broken a tuned piano wire, the now—slack wire can withstand another hit … and another. If the hits are even harder, the wire stretches more. You can almost hear the piano (and the brain under acute stress) saying, “Go on, hit me again! I can take it.” But the cost is that both are out of tune and the melody is never quite the same. In the human nervous system, this kind of adjustment or adaptation protects the brain from harm by changing the way it responds to stress. Perry and Pollard point out that repeated exposure to stress —chronic stress— results in a new way of coping with a continuous stressor, but it is less effective. Not a good thing.

Both repeated traumas and chronic stress can result in a number of biological reactions. Neurochemical systems are affected that can cause a cascade of changes in attention, impulse control, sleep, and fine motor control. Other researchers have zeroed in on specific parts of the brain that are affected by stress, and their work shows us just how refined and complex this process is. For example, Walker, Toufexis, and Davis suggest that an area of the brain called the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis plays a role in certain types of anxiety and stress responses. Although this area is not thought to be involved in acute traumatic events, these authors have shown that it is responsible for processing the slower-onset, longer-lasting responses that frequently accompany sustained threats. These authors further posit that the physiological reactions in this area may persist even after the threat goes away.

Pollard and Perry tell us that chronic activation of certain parts of the brain involved in the fear response, such as the hypothalamic—pituitary—adrenal (HPA) axis, can wear out other parts of the brain such as the hippocampus, which is involved in cognition and memory. Again, cognition and memory: two of the most important building blocks for successful learning, attention, and social communication.

–> Continued here: The frontal lobes, the little brain down under and “Stayin’ Alive” (3/3)

Dr. Jerome (Jerry) Schultz is a Clinical Neuropsychologist, author and speaker who has provided clinical services, consultation and staff development to hundreds of private and public schools in the US and abroad during his 35-year career. This is an adapted excerpt from his latest book Nowhere to Hide: Why Kids with ADHD & LD Hate School and What We Can Do About It, which examines the role of stress in learning.

Dr. Jerome (Jerry) Schultz is a Clinical Neuropsychologist, author and speaker who has provided clinical services, consultation and staff development to hundreds of private and public schools in the US and abroad during his 35-year career. This is an adapted excerpt from his latest book Nowhere to Hide: Why Kids with ADHD & LD Hate School and What We Can Do About It, which examines the role of stress in learning.

Resources to regulate stress:

Four tips to practice good mental hygiene during the coronavirus outbreak

Study finds a key ingredient in mindfulness training: Acceptance (not acquiescence)

Positive solitude, Feeling active and Future-mindednes: Three Keys to Well-being

New study reinforces the importance of walking through forests for mental and general health

Six tips to build resilience and prevent brain-damaging stress