Exploring the human brain and how it responds to stress (1/3)

__

Worry is like a rocking chair. It gives you something to do, but it gets you nowhere.

— Erma Bombeck

The brain is the control center for all of our thoughts, actions, attitudes, and emotions. It’s the pilothouse on the riverboat of our lives. It’s Mission Control for all of our flights into space or time. It’s the air traffic controller that helps us navigate and reroute our paths based on incoming and outgoing information and how we’re feeling about it at the time. It’s the John Williams of our personal symphony. It’s the Mother Ship to our Starfleet; it’s … (Uh, sorry, I got carried away there, but I think you get my point!)

As I was working on the drafts of my latest book book, my own brain was very active, to say the least.

Seriously! How was I ever going to write an introduction to the brain, the most complex organ in the human body, that you, my reader, would want to read, and that you would understand?

Hundreds of thousands of textbooks and scholarly articles contained deep and dense discussions by brilliant scientists all over the globe who were trying to explain the mysteries of this incredible organ, and I had to do it in 70,000 words!

Yet, the best way to combat stress is to gain some control over whatever it is that threatens you.

My own stress level began to go down dramatically as I realized I didn’t have to tell the entire story. I just needed to focus on the parts and systems of the brain that are most involved in the perception and processing of stress. As a neuropsychologist, I find this part of the story incredibly interesting, and hope you will as well. Trying to tell the story of stress without putting it in the context of the brain is like writing a novel without giving the characters a setting in which to act out their dramas. Without context, the reader can’t see where the action is taking place.

Putting the characters of this story —the symptoms of stress— in the context of the brain and central nervous system makes it possible to understand their nature and their purpose in a way that makes scientific sense. So … stay with me as I set the stage for an amazing tale about how the brain deals with stress.

A BRIEF TOUR OF THE HUMAN BRAIN

To most people, the brain is terra incognita, a priceless piece of neurological real estate that we’re glad we own but tend to take for granted unless or until something bad happens to it. So let’s take a brief tour, just so you can appreciate the inestimable value of this miraculous organ called the brain.

The average adult human brain weighs about three pounds (a kilogram and a half), which is a little bigger than a small cantaloupe or a large grapefruit, depending on the growing season. It starts out substantially smaller, of course, but as certain kinds of cells develop and change as a child moves into adulthood, the brain grows in size. As a result of myelination (the development of the outer coating of the long stem of brain cells, or neurons), and the proliferation of glial cells (the term glial comes from the Greek word for glue), which hold the brain together and feed it, an adult brain is about three times heavier than it was at birth. This is why you occasionally have to buy new hats.

The largest and most recognizable part of the brain is the large dome — shaped cerebrum, which is the outermost layer of brain tissue. If you lift off the skull and look down on the brain from above, it looks rather like what you see when you lift half the shell off a walnut. However, the cerebrum is not stiff like a nut; it has a thick, jelly-like consistency that allows it to literally bounce around inside the skull, which is why it ’ s so important to protect the head from encounters with immovable objects.

The largest and most recognizable part of the brain is the large dome — shaped cerebrum, which is the outermost layer of brain tissue. If you lift off the skull and look down on the brain from above, it looks rather like what you see when you lift half the shell off a walnut. However, the cerebrum is not stiff like a nut; it has a thick, jelly-like consistency that allows it to literally bounce around inside the skull, which is why it ’ s so important to protect the head from encounters with immovable objects.

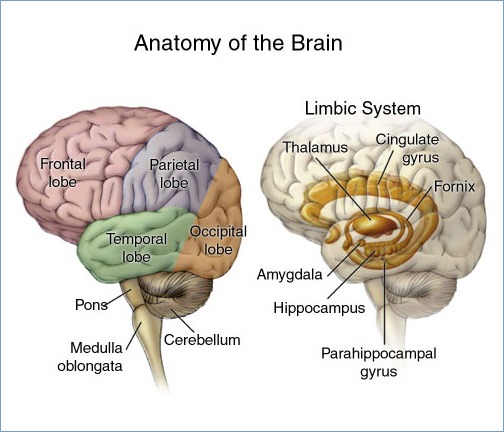

A sheet of neural tissue called the cerebral cortex forms the outermost surface of the cerebrum. It includes up to six layers, each one different in terms of the arrangement of neurons and how well they connect and communicate with other parts of the brain. The cortex is distinguishable by its many little ridges (called gyri) and valleys (sulci). In terms of space, the cortex is an economically arranged region that folds in on itself many times. This results in a very large but mainly hidden surface area that contains more neurons than any other part of the brain.

Gray Matters

The term gray matter usually evokes an image of the cortex, because that’s the part most visible in pictures of the brain. In fact, gray matter makes up not only the cerebral cortex but also the central portion of the spinal cord and areas called the cerebellar cortex and the hippocampal cortex. This dense tissue is packed full of neuronal cells, their dendrites (branching, root — like endings), axon terminals (the other end), and those sticky glial cells I mentioned earlier. The cortex is the area of the brain where the actual processing of information takes place. Because of its relative size and complexity, it ’ s easy to understand why it plays a key role in memory, attention, perceptual awareness, thought, language, and consciousness.

A Division of Labor

A central groove, or fissure, runs from the front to back of the cortex, dividing it into right and left hemispheres. In general, the left hemisphere controls functions on the right side of the human body and the right hemisphere controls the left side, but there are significant exceptions and much sophisticated interaction between the two hemispheres. This communication between the left and right hemispheres is facilitated by the corpus callosum, a wide, flat bundle of axons located in the center of the brain, beneath the cortex. Think of it as the Lincoln Tunnel, connecting Manhattan and Jersey City. (I’ll leave it to you to decide which one represents which hemisphere.)

The corpus callosum makes up the largest area of so—called white matter in the brain. White matter is made of bundles of axons each encased in a sheath of myelin. These nerve bundles lead into and out of the cortex and the cerebellum, and branch to the “ old brain, ” the hippocampus. About 40 percent of the human brain is made up of gray matter, and the other 60 percent is white matter. It’s the white matter that facilitates communication between different gray matter areas and between the gray matter and the rest of the body. White matter is the Internet of our brains. (Al Gore did not invent it.)

Evolution, tempered by experience, has employed gray matter to build what might be considered very well—developed “cognitive condos” that sit above the hippocampus. This arrangement is very important to a discussion of stress. Our old or primitive brain was primed for survival in our ancestors’ environment. It’s interesting to note that the brains of lower vertebrates like fish and amphibians have their white matter on the outside of their brain. We are blessed (and cursed) with lots of gray matter that gives us the ability to think things through (especially if we are anxious). Frogs and salamanders and their pond—side friends don’t think about danger so much — they just get out of its way! (And while I can’t be sure, I don’t think that they have nightmares about giant human children armed with nets.)

How do you feel about that? In case you ever get this question on Jeopardy or in a game of Trivial Pursuit, the limbic system is made up of the amygdala, the hippocampus, the cingulate gyrus, fornicate gyrus, hypothalamus, mammillary body, epithalamus, nucleus accumbens, orbitofrontal cortex, parahippocampal gyrus, and thalamus. These structures work together to process emotions, motivation, the regulation of memories, the interface between emotional states and memory of events, the regulation of breathing and heart rate, the production of hormones, the “ fight or flight ” response, sexual arousal, circadian rhythms, and some decision—making systems. Pretty impressive job description, eh?

The word limbic comes from the Latin word limbus, which translates to “belt” or “border,” because this system forms the inner border of the cortex. The limbic system is part of the old brain and developed first, followed by the new brain: the cortex, which is sometimes referred to as the neocortex. Put simply, the limbic system feels and remembers; the cortex acts and reacts. And they communicate with each other. Why is this important? The limbic system figures prominently in what’s called the stress response.

These days, both our old and new brains are activated when we’re under stress. The primitive part, the limbic system (notably the hippocampus), sniffs out danger well before the new brain (the neocortex) actually processes it. The old brain responds first, acting as a sort of fire alarm system. It is the neocortex, and in particular, the frontal lobe (the pre-frontal cortex), that helps us make sense of the alarms.

–> Continued here: On World Health Day 2020, let’s discuss the stress response and the General Adaptation Syndrome (2/3)

Dr. Jerome (Jerry) Schultz is a Clinical Neuropsychologist, author and speaker who has provided clinical services, consultation and staff development to hundreds of private and public schools in the US and abroad during his 35-year career. This is an adapted excerpt from his latest book Nowhere to Hide: Why Kids with ADHD & LD Hate School and What We Can Do About It, which examines the role of stress in learning.

Dr. Jerome (Jerry) Schultz is a Clinical Neuropsychologist, author and speaker who has provided clinical services, consultation and staff development to hundreds of private and public schools in the US and abroad during his 35-year career. This is an adapted excerpt from his latest book Nowhere to Hide: Why Kids with ADHD & LD Hate School and What We Can Do About It, which examines the role of stress in learning.

Resources to regulate stress:

Four tips to practice good mental hygiene during the coronavirus outbreak

Study finds a key ingredient in mindfulness training: Acceptance (not acquiescence)

Positive solitude, Feeling active and Future-mindednes: Three Keys to Well-being

New study reinforces the importance of walking through forests for mental and general health

Six tips to build resilience and prevent brain-damaging stress