Study finds clear–yet surprisingly different–benefits in 3 types of meditation-based mental training

___

___

As citizens of the 21st century, we face many problems that come with an industrialized and globalized world. I’m not a lawyer or a politician, but a psychologist and neuroscientist. So research on how to train helpful mental and social capacities is my way to contribute to a more healthy, communal, and cooperative civilization.

For the past five years, that research has taken the form of the ReSource Project, one of the longest and most comprehensive studies on the effects of meditation-based mental training to date. Lots of research treats the concept of meditation as a single practice, when in fact meditation encompasses a diversity of mental practices that train different skills and different parts of the brain. Our goal was to study the specific effects of some major types of mental practices and distinguish their effects on well-being, the brain, behavior, and health—and, in particular, discover which practices could help build a more compassionate and interconnected world.

The results so far have been mostly encouraging, sometimes surprising, and crucial to understand for meditation practitioners and teachers.

Three types of meditation-based mental training

In the ReSource Project, we asked over 300 German adults ages 20–55 to attend a two-hour class every week and practice for 30 minutes a day at home. The lessons and practices were designed by myself together with an expert team of meditation teachers and psychologists over the course of several years. They include a multitude of secularized meditations derived from various Buddhist traditions, as well as practices from Western psychology. Over the course of the study, participants moved through three different training modules, which each began with a three-day retreat:

- Presence (3 months). This module focuses on training attention and internal body awareness. The exercises include scanning your body, focusing on the breath and bringing your attention to the present moment whenever your mind wanders, and bringing attention to the sensations of hearing and seeing.

- Affect (3 months). This module focuses on training positive social emotions like loving-kindness, compassion, and gratitude, as well as accepting difficult emotions and increasing our motivation to be kind and helpful toward others. In the Affect and Perspective modules, there are two daily core practices: one classic meditation and one 10-minute partner exercise, with participants assigned to a new partner every week on our mobile application. In the Affect module, partners take turns sharing their feelings and body sensations while recalling difficult or gratitude-inducing experiences in their lives, and practicing empathic listening.

- Perspective (3 months). This module focuses on meta-cognitive skills (becoming aware of your thinking), gaining perspective on aspects of your own personality, and taking the perspective of others. In this module, the partner exercise includes taking turns talking about a recent experience from the perspective of one aspect of your personality—for example, as if you were fully identified with your “inner judge” or “loving mother”—while the other partner listens carefully and tries to infer the perspective being taken.

Three cohorts moved through these modules in different orders, allowing us to discern the effects of a specific training module and compare it to the other modules. In other words, the cohorts acted as “active control groups” for each other. Another group of participants didn’t do any training but was still tested: Every three months, we measured how participants were doing with a barrage of more than 90 questionnaires, behavioral tests, hormonal markers, and brain scans, to see what (if anything) improved after each module.

When I first launched this study, some of my colleagues thought a year-long mental training course was crazy, that participants would drop out right and left. But that’s not what happened: In fact, less than 8 percent of people dropped out in total.

The multiple–and surprisingly different–benefits for each practice

We found that the three training modules had very different effects on participants’ emotional and cognitive skills, well-being, and brains—which means that you can expect different benefits depending on the type of meditation practice you engage in.

We found that the three training modules had very different effects on participants’ emotional and cognitive skills, well-being, and brains—which means that you can expect different benefits depending on the type of meditation practice you engage in.

Attention. According to our study, attention already improved after just three months of training, whether it was mindfulness-based or compassion-based. Participants who completed the Presence or Affect modules significantly improved their scores on a classic attention task. It seems, therefore, that attention can be cultivated not only by attention-focused mindfulness practices but also by social-emotional practices such as the loving-kindness meditation.

Compassion. In our study, one of the ways we measured compassion was by showing participants videos of people sharing stories of suffering from their life and asking them to report how they felt after watching. Ultimately, three months of attention-based Presence training didn’t increase compassion at all. Only participants who had taken the Affect module—which explicitly focuses on care-based social and emotional qualities—became more compassionate.

Theory of mind. If we want to resolve conflicts across cultures, theory of mind—the ability to understand other people’s mental states and put ourselves in their shoes—is a crucial skill. We measured theory of mind with the same video stories, but this time we asked participants to answer questions about the person’s thoughts, intentions, and goals. It turned out that only one module—the Perspective module—helped participants improve their theory of mind at all (though these effects were not strong). Practicing attention or compassion in the Presence or Affect modules didn’t help people take the perspective of others.

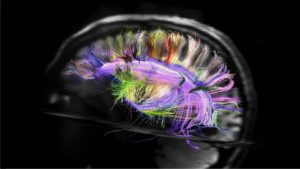

Brain plasticity. These different behavioral changes were also reflected in the brain. Using magnetic resonance imaging, my colleagues and I analyzed the volume of gray matter in different areas of participants’ brains.

Brain plasticity. These different behavioral changes were also reflected in the brain. Using magnetic resonance imaging, my colleagues and I analyzed the volume of gray matter in different areas of participants’ brains.

Typically, gray matter thins over time as people age. But after three months of attention-based Presence training, participants actually showed a higher volume of gray matter in their prefrontal regions, areas related to attention, monitoring, and higher-level awareness.

After three months of compassion-based Affect training, however, other regions became thicker: areas that are involved in empathy and emotion regulation, such as the supramarginal gyrus. Most importantly, this thickening in insular regions of the brain predicted increases in compassionate behavior.

Finally, we observed specific thickening in another set of brain regions after the Perspective module. Gray matter in the temporo-parietal junction, an area that supports our perspective-taking abilities, became thicker in people who also improved at theory of mind tests. This is the first study to show training-related structural changes in the social brains of healthy adults and to reveal that it really matters what you practice—the observed brain changes were specific to different types of training and coincided with improvements in emotional and cognitive skills.

Social stress. To measure social stress, we gave participants a notoriously stressful task: delivering a speech and then performing math calculations to an audience trained to roll their eyes, look bored, and point out errors. This makes people feel socially rejected and out of control, like something is wrong with them; it stimulates most people’s bodies to produce a lot more of the stress-related hormone cortisol, which we measured in saliva.

Three months of mindfulness-based attention and internal body awareness training didn’t help people cope better with this stressful task. But those who practiced the two social modules, Affect and Perspective, did reduce their cortisol stress response by up to half compared to the control group. We suspect that the daily partner practices in these modules helped ease people’s fear of being evaluated. We face potential evaluation by others every day, and learning to listen non-judgmentally and to be less reactive probably allows us to approach those socially stressful situations more calmly.

The fact that the mindfulness-based Presence module did not reduce stress at the hormonal level was surprising at first, since previous research has shown that mindful attention training can reduce stress. But much of this earlier research asks people about their stress levels with questionnaires, rather than measuring biological markers of stress. When using questionnaires, we found the same thing: After three months of Presence practice, people said they felt less stressed, as they did after all the other modules. Even though it certainly matters how stressed people subjectively feel, cortisol is considered the hallmark of a stress response and is linked to important health outcomes. Given that this was not reduced by mindfulness attention training alone, we should be wary of generalized claims about its stress-reducing effects.

Some effects take time to develop—something we should remember whenever we sign up for a weekend meditation course or download a new meditation app promising us big results in just a few minutes or days!

What’s next

To summarize, mindfulness and meditation are incredibly broad concepts, and our research suggests that they should be differentiated more. It really matters what type of mental practice you engage in. Different types of mental training elicit changes in very different domains of functioning, such as attention, compassion, and higher-level cognitive abilities.

The good news is that with only about 30 minutes of practice a day, you can significantly change your behavior and the very structure of your brain. However, some improvements take time to develop. Even nine months is just a start.

The story about meditation and mindfulness will become more complex over the years. Besides looking at the different effects of different types of mental practices, researchers are also exploring individual differences and how certain genes or certain personality traits influence how much you benefit from different practices. All of this research is moving us to a point where we don’t necessarily advocate mindfulness for all, but can suggest specific practices with specific benefits for specific people.

The story about meditation and mindfulness will become more complex over the years. Besides looking at the different effects of different types of mental practices, researchers are also exploring individual differences and how certain genes or certain personality traits influence how much you benefit from different practices. All of this research is moving us to a point where we don’t necessarily advocate mindfulness for all, but can suggest specific practices with specific benefits for specific people.

In an increasingly complex world, one of today’s most urgent questions is how we can cultivate greater global compassion and a better understanding of each other across cultural and religious divides. Training that focuses on the interdependence of human beings, on ethical as well as social qualities—from feelings such as compassion to cognitive skills like perspective taking—may be important not only for individual health but also for communal flourishing.

This essay is adapted and condensed from a talk by Tania Singer, “Plasticity of the Social Brain: Effects of a One-Year Mental Training Study on Brain Plasticity, Social Cognition and Attention, Stress, and Prosocial Behavior,” given at the International Positive Psychology Association’s 5th World Congress in 2017. Based at UC-Berkeley, Greater Good highlights ground breaking scientific research into the roots of compassion and altruism. Copyright Greater Good.

The Study

Differential Benefits of Mental Training Types for Attention, Compassion, and Theory of Mind (Mindfulness)

- Description: Mindfulness- and, more generally, meditation-based interventions increasingly gain popularity, effectively promoting cognitive, affective, and social capacities. It is unclear, however, if different types of practice have the same or specific effects on mental functioning. Here we tested three consecutive three-month training modules aimed at cultivating either attention, socio-affective qualities (such as compassion), or socio-cognitive skills (such as theory of mind), in three training cohorts and a retest control cohort (N = 332). While attention performance improved across the training modules, compassion increased most strongly after socio-affective training and theory of mind showed selective improvements after socio-cognitive training. These results show that specific mental training practices are needed to induce plasticity in different domains of mental functioning, providing a foundation for evidence-based development of more targeted interventions adapted to the needs of different education, labor, and health settings.

The Study in Context

- The State of Mindfulness Science: 10 Key Research Findings to Encourage and Guide your Meditation Practice in 2018

- Learning how to mindfully navigate mindfulness apps

- Can brain training work? Yes, if it meets these 5 conditions

- Digital Mental Health: the Hurt, the Hype, the Hope, with Dr. Tom Insel