“I am excited”: Making Stress Work for You, Instead of Against You

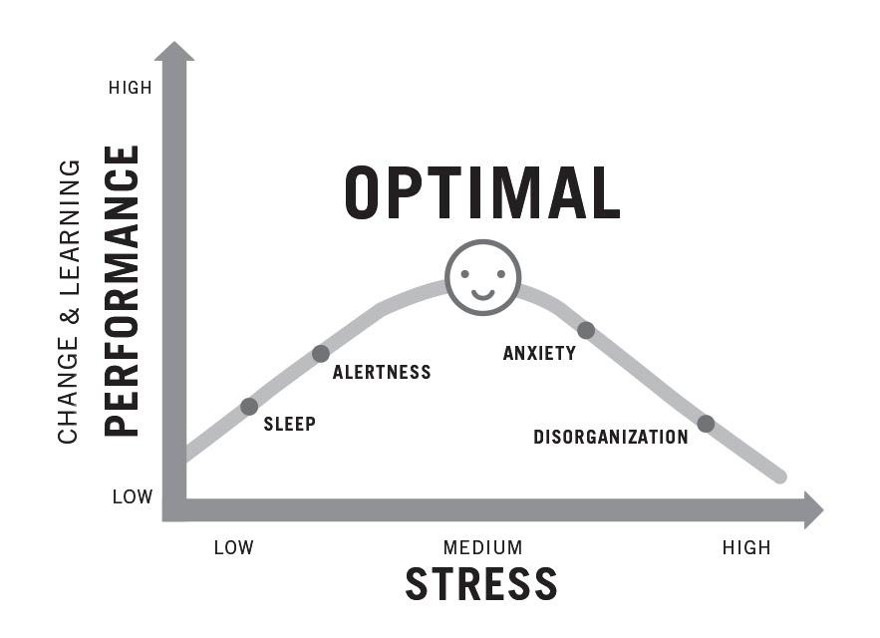

Image: The Yerkes-Dodson Law (YDL)

—

How much stress is good for you?

In 1908, Robert Mearns Yerkes and John Dillingham Dodson designed an experiment that would begin to tackle the question, “How much stress is good for you?”

The researchers tracked mice to see how stress would affect their ability to learn. Simple—yet painful, because how do you stress out mice? You shock them. The researchers set up two corridors to choose from—one painted white and the other black—and if a mouse went down the black corridor, ZAP! Yerkes and Dodson observed that given too mild a shock, the mice just shrugged it off and kept on keepin’ on—no biggie if they made the same mistake again. Too big a jolt, and the stress left them too frazzled too figure out what had just happened and how to make that not happen again. Those who learned most quickly—indeed, those mice that might need half as much time to learn which corridor to take—did it Goldilocks style: the size of their shock was juuuuust right.

You may not be a mouse, but research shows that you learn like one.

Not that we are suggesting self-electrocution (to do so would be highly unethical—fascinating, but highly unethical). But a just-right dose of stress can lead to your peak performance. Ed Ehlinger of the University of Minnesota studied almost 10,000 students and found that those who couldn’t manage their stress (32 percent of them) had a 0.5 drop in their GPA compared to their less-stressed-out peers. Imagine if getting your ZAP on in just the right way enabled you to learn math/English/anything-else-you-want in less time and learn it better.

The Yerkes-Dodson experiments have risen to prominence as the Yerkes-Dodson Law (YDL) and have become the key to understanding the relationship between stress and our ability to change, learn, and perform. The YDL even comes with a handy-dandy YDL curve (see above) that helps us understand how to think about stress in relation to our performance in college and beyond.

One of the many beauties of the YDL curve is its simplicity: if you have too little stress (the left side of the curve) or too much stress (the right side), you miss out on opportunities to learn, change, perform, or basically do anything in college to help realize your potential. Simple? Yes. Pertinent? Very.

Kristen Joan Anderson, a psychologist at Northwestern University, did her version of the mouse-ZAP study on 100 college students, giving them escalating amounts of caffeine and having them answer questions like the ones in the verbal section of the Graduate Record Examinations (GREs). She found that many college students (and the rest of us), particularly with difficult tasks, perform their best at levels of stimulation that look a lot like the YDL curve (for those interested: about two cups seems to do it).

Interestingly, though, a feeling of control over stress profoundly impacts the effects of being stressed out. A 2015 study about stress and its impact on test scores found that, regardless of how “stressed out” the students really were, if they felt they could handle it, their grades were not impacted. For many of us, realizing that stress isn’t going to be a lifelong enemy gives us a sense of control. The stress may stick around, in varying degrees, but your suffering can be diminished in a very big way. How you relate to, tolerate, and manage stress in any given situation dictates how well you can take advantage of it.

One Solution: Get Excited to Stay Calm

If you are thinking that trying to keep calm is the way to go when you are stressed out, welcome to the vast majority. Harvard Business School professor Alison Wood Brooks found that 85 percent of people advise calm in the face of the storm. Yet not only does that not work, it actually has the opposite effect.

In a study using the classic combination of college students and karaoke, Brooks found that telling oneself to chillax is in fact a stress generator. She asked college students to perform karaoke in public, but before they went onstage, the subjects were divided into three groups and primed with one of three ideas: say nothing, say “I am excited,” or say “I am anxious.” Kind of like in an audition for The Voice, subjects were rated for pitch, volume, and rhythm by both computers and researchers (sadly, none of whom resembled Adam Levine or Shakira). The “I am anxious” group scored 53 percent, the lowest, apparently freaking themselves out and showing that certain self-statements can do more harm than good. If they were told to say nothing, their average score was 69 percent.

But the “I am excited” group scored an average of 81 percent. When you can harness your challenge response, you can take advantage of your physiology and your mind, and you can kill it!

The “I am excited” group felt just as much anxiety as the “I am anxious” group and the group that said nothing, but they also felt more capable and were observed by their audience to be more confident. Feeling that you have control over stress doesn’t mean you stop “feeling” it. If you need to be intoxicated to perform karaoke, this experiment might not seem believable to you, but Brooks also studied people who had to give a speech or perform math problems. Same results: better performance and an even greater feeling of competence.

We are not saying you will enjoy swimming with sharks if you just say “I am excited.” There is a time and place for you to actually fight or flee. But the next time something is at stake (other than your actual life) and you feel butterflies in your stomach and your heart pounding, remember that feeling scared and feeling excited often go hand in hand, and choosing one over the other (literally just saying out loud “I am excited”) will make all the difference.

– This is an excerpt from U Thrive: How to Succeed in College (and Life) (Little and Brown, April, 2017), by Dan Lerner and Dr. Alan Schlechter. Dan Lerner is a strengths-based performance coach, teacher and speaker, on the faculty at New York University (where he co-teaches “The Science of Happiness”) and the University of Pennsylvania (where he works with the graduate program in Applied Positive Psychology). Dr. Alan Schlechter, is the Director of the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic at Bellevue Hospital Center. In his role as Director he treats and helps organize the care of some of the most vulnerable children and families in New York City.

Related articles: