5 ideas to help knowledge workers increase lifelong learning and productivity

—–

—–

Some apps aim to help you train specific brain functions, such as working memory. Others are meant to help you maintain specific skills, such as useful field of view for safe driving. But suppose you are reading a very insightful book and need to master some of its knowledge gems.

What kind of app might you use?

Let’s discuss the problem first, and then the opportunity.

The Problem: As we get older, we often abandon deliberate practice

Copious research has shown that an excellent way for students to comprehend material and prepare for exams is to test themselves on course material at spaced intervals. Why should this work? First, it compels students to identify and focus on the knowledge they need to acquire. That knowledge determines the questions they should practice answering.

Second, self-testing helps the brain answer an important problem that it implicitly asks itself overnight: “Of all the information I have processed recently, what information must I prioritize for learning?” In constructing its complex indexes, the brain gives higher priority to information you have practiced recalling or using unaided. It’s as if the brain tells itself “I’d better make this information easy to access in the future because I am likely to be called upon to use it again.” In contrast, if you merely re-read information, your brain will implicitly assume that if it needs the information in the future, it can get it from the text. That’s why re-reading a chapter or a poem doesn’t work very well.

Deliberate practice has also been shown to be essential to the development of expertise. Chess masters, professional athletes and musicians perform well largely because they practice adeptly and often.

Alas, after they graduate people tend to abandon deliberate practice. After reading important material, most don’t bother to test themselves to ensure they can use it later. Why? People tend to assume that they will be able to remember and use information they have carefully read. Also, professors teach content, they rarely teach or assess learning strategies. Most students study merely for exams whose questions are set by professors.

Unlike real life, the dates and content of university exams are predictable. A physics exam does not contain psychology questions. In life, at random times you might need access to previous random knowledge. Real life learning isn’t merely about recalling or explicitly using information. You might want to develop new goals, perceptions, habits, attitudes and ways of being in the world. Professors can’t assess how well students apply knowledge in their personal or professional lives.

Culture also has made it difficult for graduates to combine the benefits of test-enhanced learning and deliberate practice. Test-enhanced learning and deliberate practice are rarely discussed together. Whereas our culture prizes practice in public performance disciplines (like music and sports), it is hardly researched or discussed in the context of knowledge work and soft skills. Practicing is taboo. Also, popular books about practicing and self-testing don’t explain how to use apps for this purpose. Yet most information comes to us through technology.

To make matters worse, software needed to practice productively has not been adequately designed or integrated with apps for reading and viewing. (This was the subject of one of the first articles about the iPad, which I wrote for SharpBrains in 2010.)

The Solution: Help knowledge workers use screen time better

However, it is possible to leverage information technology and cognitive science to practice productively. Productivity is a key requirement here because many, perhaps most, knowledge workers already spend more time with technology than they should. To introduce practice into their routine, it needs to replace some of their screen time, not add to it.

In my recent book, Cognitive Productivity: Using Knowledge to Become Profoundly Effective, I propose the following 5 ideas:

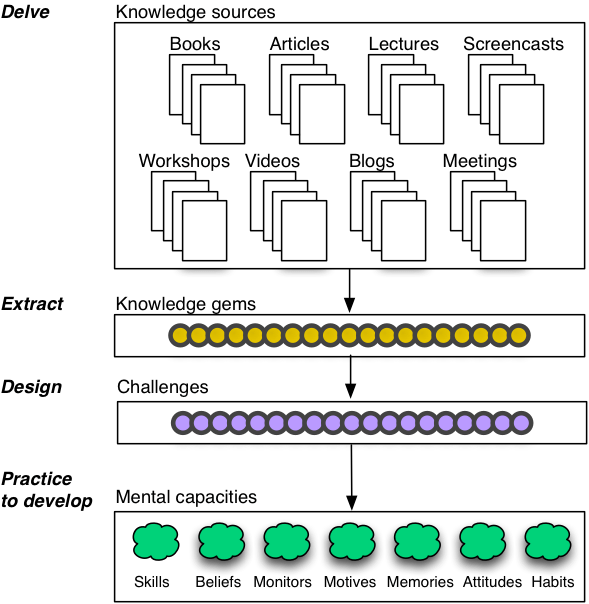

- Significantly reduce time spent processing less relevant information.

- Focus on helpful information that is worth ‘delving into’.

- From this information, every week, pick out knowledge gems

- Develop ‘challenges’ (question and answer pairs’) to practice using a self-testing app (e.g., a very versatile flashcard app.) Design these challenges in such a way as to give you the outcomes you want (rapidly accessible memories, habits, attitudes, etc.)

- Spend time several days a week practicing with your self-testing app.

The following figure illustrates this process.

This system works for the same reasons as self-testing works for students. It forces you to attend to the most relevant information. Practicing indicates to your brain that the practiced information matters to you.

Such self-directed learning calls for major components of lifelong learning and brain health outlined in The SharpBrains Guide to Brain Fitness: initiative, self-monitoring, prioritizing and cognitive training.

In short, we need a new culture for knowledge workers of any age to combine the benefits of test-enhanced learning and deliberate practice.

Let’s practice right now…what knowledge gem are you going to extract from this article?

— Dr. Luc Beaudoin is an Adjunct Professor of Cognitive Science and Education at Simon Fraser University. A self-described productivity geek, with a PhD in Cognitive Science from the University of Birmigham in England, he recently wrote Cognitive Productivity to explain how to use software to process knowledge resources, extract knowledge gems, and practice productively.

— Dr. Luc Beaudoin is an Adjunct Professor of Cognitive Science and Education at Simon Fraser University. A self-described productivity geek, with a PhD in Cognitive Science from the University of Birmigham in England, he recently wrote Cognitive Productivity to explain how to use software to process knowledge resources, extract knowledge gems, and practice productively.

Related article: