What Everyone Should Know About Stress, Brain Health, and Dance

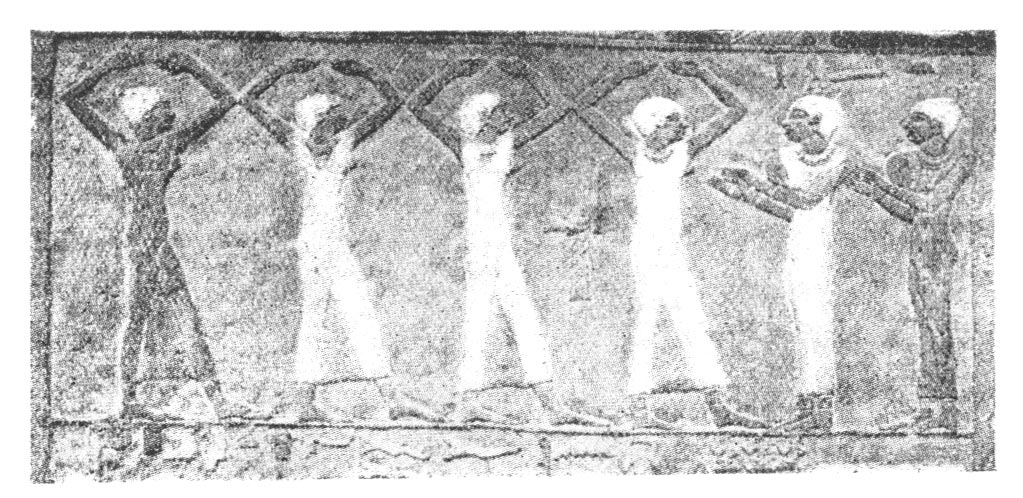

– Dancing to the clapping of bands. Egyptian, from the tomb of Ur-ari-en-Ptah, 6th Dynasty, about 3300 B.C. (British Museum)

Everyone experiences stress at some point in our lives. It is important to know that stress can harm the brain, and also that dance can be a great avenue for a person resist, reduce, or escape it.

Stress can change the physical structure and function of the brain, affecting wiring and thus performance of one’s activities. Formation of new neural connections in the hippocampus, responsible for encoding new memories, becomes blocked. This blockage hinders the mental flexibility needed to find alternative solutions and negatively affects attention, memory, and other cognitive functions, motivation, and energy. Long-term and also short-term stress, even a mere few hours, can reduce cellular connections in the hippocampus, shrinking it.

How stress can harm the brain

Stress occurs when individuals have to cope with demands that require them to function above or below their usual level of activity. Everyday worries and pressures or the anticipation of a threatening situation, or extraordinary excitement, as well as emergencies, may trigger the response. The amygdala, via the pituitary gland, stimulates the hypothalamus to send a message to adrenal glands that spill out stress hormones. These activate the fight-or-flight response, increasing the production of the inflammatory hormones adrenaline (epinephrine) and cortisol, which work together to speed heart rate, to increase metabolism and blood pressure, to shunt blood way from organs into muscles, lower pain sensitivity, and to enhance attention, all beneficial for survival.

After the body has mobilized for the alarm reaction, and the stressful situation is coped with, the second phase of the stress response kicks in. The adrenal cortex produces anti-inflammatory hormones that limit the extent of inflammation against stressors and return the body to normal.

However, when a person is under chronic distress, that fight-or-flight reaction stays, turned on and prevents the body from returning to normal. High adrenaline and cortisol levels that persist cause ill health — both physical and cognitive harm.

The role of dance in promoting brain health

Dance has been a medium to cope with stress through history and across geographical space. Humans have long held dance as a key tool in their toolkit to resist, reduce, or temporarily escape stress. Dance-stress connections are played out in social life, on theater stages, in the professional dance career, in amateur dance, and through therapeutic interventions.

Dance exercise may lead to increased levels of norepinephrine and endorphins, and dissipate the harmful biochemical elements of energy that can remain in the body when you neither fight nor flee from stress because physical action is impossible. Movements increase blood and oxygen flow to the brain, contributing to alertness, and trigger the chemical brain-derived neurotropic factor that supports the health of young neurons, encourages the growth of new ones, and fortifies connections among neurons.

Dance exercise may lead to increased levels of norepinephrine and endorphins, and dissipate the harmful biochemical elements of energy that can remain in the body when you neither fight nor flee from stress because physical action is impossible. Movements increase blood and oxygen flow to the brain, contributing to alertness, and trigger the chemical brain-derived neurotropic factor that supports the health of young neurons, encourages the growth of new ones, and fortifies connections among neurons.

As physical activity dance sparks neurogenesis. Dance generates neurons that nimbly wire into the neural network. More complex movements lead to more complex synaptic connections, and dance has multiple levels of complexity.

Being exercise-plus, dance helps us cope with negative stress as a way of knowing, thinking, translating, interpreting, communicating, and creating thought. Going beyond physical movement, dance conveys ideas and feelings, tells stories, and communicating with multiple parts of the body in various ways. Dance requires learning moves, sequences, and meaningful interpretation.

Pundit David Brooks compared dancing with the Olympics: “Dance is physical, like sports, but, in many ways, it is the opposite of sports. In dance, the purpose is to blend with and mirror each other; in sport, the purpose is to come out ahead. Dancers perform for the audience [and for themselves] and offer a gift of emotion; athletes respond to one another and the spectators are just there to witness and cheer.”

Use of the story telling capability of dance is one of the experiential methods to release a person from bad thoughts and behavior. In dance people can recount stressful situations, holding them up for reevaluation and creating versions of the stories in pleasurable ways. Taboo themes can be held up for scrutiny and confronted safely. After all, dance is only pretend, a venue in which to dream oneself anew, even with abstract dances into which meaning can be read by dancer and spectator.

Dance has the potential to reactivate the emotional learning underlying the person’s negative patterns. The dance leader/teacher/therapist finds a vivid contradictory knowledge or experience to disconfirm and dissolve the past learning and then combine the two into a juxtaposition experience of new learning. Repetition serves as new learning that rewrites the negative learning.

Moreover, exercise can reduce depression, anxiety disorders, and pain. Altering moods improves mental health, and thus blunts the stress response. Apparently exercise also releases a copious quantity of magical, morphine-like brain chemicals, such as opiate beta-endorphins, that produce feelings of calm, satisfaction, euphoria, and greater tolerance for pain.

Dancing may be a kind of stress inoculation. With its need for strength, flexibility, and endurance, dance also promotes fitness. An individual adapts to the increase in heart rate, blood pressure, and stress hormones experienced during dancing, and consequently can better resist stress. So dance to resist, reduce, or escape negative stress and maintain your brain health!

Next steps to dance away stress

There are many venues for dance, different genres with their musical accompaniment, and various levels depending on one’s experience. If one is physically fit, dance that is aerobic lasting more than 30 minutes several times a week appears to be most beneficial. However, even dance with modest intensity and amounts is advisable. Non-dancers have their own tolerance for adventures into the unknown, but the internet allows a preview of types of dance and venues close to you. For a healthy life, keep trying until you find what feels right.

—————————

Judith Lynne Hanna, PhD, is author of Dancing to Learn: The Brain’s Cognition, Emotion, and Movement and a former California-certified social studies and English teacher who has taught dance.

Judith Lynne Hanna, PhD, is author of Dancing to Learn: The Brain’s Cognition, Emotion, and Movement and a former California-certified social studies and English teacher who has taught dance.

–> Editor’s Note: You can join Judith in discussing these topics during the Arts and the Brain Series, April 7, 2016, Thursday at 7:30 in the Mansion, Strathmore performing arts center, Rockville, Maryland.

To learn more: