Trend: School-based programs to enhance resilience and emotional/ cognitive flexibility

—

—

Dozens of programs to encourage resilience have been introduced in schools all over the world, both to help children recover from trauma, but also cope better with their day-to-day stresses. Many use techniques such as ‘mindfulness’, which some claim can foster a stronger state of mind. Meanwhile, researchers have been studying adults who have thrived under severe stress to try and identify what it takes to be truly resilient. Can you really teach people to be mentally tougher?

For scientists the concept of psychological resilience began in the 1970s with studies of children who did fine – or even well in life – despite significant early adversity, such as poverty or family violence. For a long time a person’s level of resilience was thought to be inherited or acquired in early life. This idea was supported by the often-replicated statistics on what happens after a trauma: while most people bounce back to normal relatively quickly, and some even report feeling psychologically stronger afterwards than they did before, about 8% develop post-traumatic stress disorder, according to US figures.

Dennis Charney at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City and Steven Southwick at the Yale School of Medicine have avidly studied people to find out why some are more resilient than others.

Extreme stress

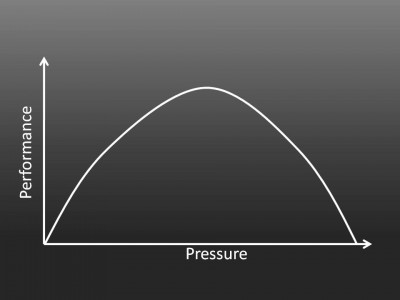

People whose bodies respond rapidly to a threat – with a surge of the stress hormones adrenaline, noradrenaline and cortisol – but who then recover quickly seem to cope better with stressful situations and jobs, such as working in the military.

More resilient people also seem to be better at using the hormone dopamine – which has a role in the brain’s reward system – to help keep them positive during stress. Researchers working with US Special Forces soldiers have found that the amount of activity in the reward systems of the soldiers’ brains remained high when they lost money in an experimental game, unlike in the brains of regular civilian volunteers. This suggests the system in resilient people’s brains may be less affected by stress or adversity. Each of the soldiers’ brains also featured a healthily large hippocampus (which as well as enabling the formation of new memories also helps regulate the release of the fight-or-flight hormone adrenalin) and a strongly active prefrontal cortex, the brain region dubbed ‘the seat of rational thinking’. This in turn helps inhibit the amygdala, the part of the brain that processes negative emotions such as fear and anger, allowing the prefrontal cortex to come up with a sensible plan to cope with a threat.

Through their research, Charney and Southwick have identified 10 psychological and social factors that they think make for stronger resilience, either alone or ideally in combination:

- facing fear

- having a moral compass

- drawing on faith

- using social support

- having good role models

- being physically fit

- making sure your brain is challenged

- having ‘cognitive and emotional flexibility’

- having ‘meaning, purpose and growth’ in life

- ‘realistic’ optimism.

Charney and Southwick are convinced that it is possible to develop these 10 factors, and that this can lead to a positive change for generally healthy people in their ability to cope not just with a major trauma, but also with the day-to-day stresses of life. One technique, in particular, might help people with this development. Until recently this technique was relatively obscure. Now it’s everywhere: mindfulness.

Mindfulness has its origins in the Zen Buddhist tradition, but its central ideas – involving attention and awareness – are secular. A modern explanation is that it means paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgmentally, to the unfolding of experience, moment to moment.

Mindful practice

Lantieri believes that mindfulness and other fundamental stress-reducing strategies are vital foundations for the kinds of changes Charney talks about. “Many of the factors he mentions are internal strengths that can be cultivated through mindfulness – such as cognitive and emotional flexibility or facing fear. We can’t just tell people that it’s better to face their fear without helping them figure out how,” she says.

Lantieri’s is one of the longest-running ‘resilience-building’ programs for schools, but it isn’t the only one out there. The concept of resilience – both in schools and beyond the classroom – is a hot one. In February 2014 a UK cross-party government group produced a report calling for schools to promote “character and resilience”. May 2014 saw the launch of an all-party group to explore the potential for mindfulness in education, as well as in health and criminal justice.

Lantieri’s is one of the longest-running ‘resilience-building’ programs for schools, but it isn’t the only one out there. The concept of resilience – both in schools and beyond the classroom – is a hot one. In February 2014 a UK cross-party government group produced a report calling for schools to promote “character and resilience”. May 2014 saw the launch of an all-party group to explore the potential for mindfulness in education, as well as in health and criminal justice.

Mark Williams, director of the Oxford Mindfulness Centre at the University of Oxford, is the joint-developer of a technique for treating depression called mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. It involves encouraging patients to be aware of their thoughts and to accept them, without judgement. Research shows that it may be as effective as drugs at cutting the chances of a person who’s experienced one episode of major depression from suffering another.

And Martin Seligman (sometimes dubbed the ‘father of positive psychology’) and a team at the University of Pennsylvania have developed the Penn Resiliency Program for late elementary and middle school students. Here the focus is on the content of thoughts. Over 12 sessions lasting 90 minutes, students are taught to detect ‘inaccurate’ thoughts, evaluate the accuracy of them and challenge negative beliefs by considering alternative explanations (that popular girl just ignored me in the corridor because she didn’t see me, not because she hates my guts). Students are also taught techniques for assertiveness, negotiation, decision-making and problem solving, as well as relaxation.

On what evidence?

But do these programs work? The effects of Mindfulness in Schools curriculum – rolled out in six participating schools – have been scrutinised in a pilot study conducted by Willem Kuyken at the University of Exeter along with other researchers who have worked with Williams. The results, published in the British Journal of Psychiatry in 2013, found that the curriculum had promising – but small – effects on stress levels and wellbeing. The researchers would like to investigate this further in a large-scale randomised controlled trial of the curriculum in British secondary schools.

The Penn Resiliency Program has been evaluated in the US and the UK, and again the effects are small, although statistically significant. There was a “small average impact on pupils’ depression scores, school attendance and English and maths grades”, according to the UK report, but this only lasted until the one-year follow-up study. By the two-year follow-up its impact had vanished.

This doesn’t mean the programs aren’t useful, says Kuyken. Studies that involve giving an intervention to everybody, whether or not they have a problem, generally only get small overall results. “What these interventions have the potential to do is move the bell curve – that is, to help those most at risk of depression at one end of the curve, but also those who are flourishing and those in the middle who represent most people,” he says.

Still, there’s no silver bullet when it comes to resiliency in kids, says Ron Palomares, a school psychologist at Texas Woman’s University. Between 2000 and 2013 he worked on the American Psychological Association’s Road to Resilience campaign, which it set up after 9/11 to provide public information on how to become more resilient. For adolescents with depressive symptoms, perhaps the Penn Resiliency Program approach may work best, he says. The mindfulness programs being developed in schools in the US and the UK are focused more on emotional regulation, which some kids may need help with but others won’t.

The multifaceted approach of the Lantieri’s Inner Resilience Programme (IRP), meanwhile, may be best for a group, like an entire school, because it’s more likely to cover the various needs of most of the pupils. Yet, compared to the formal programs, Lantieri’s IRP is more of a ‘bag of tricks’ – or “a bag of practical strategies” – as she describes it. She says she wants to give adults and kids options, as many as possible, to help children cope with whatever life throws at them. “As much as we like to think we can protect our children from what may come their way, we live in a very complex and uncertain world,” she says. “We have to give them all the skills of inner resilience, so they’re ready for just everyday life.”

– Emma Young is an award-winning science and health journalist. A former reporter and editor on New Scientist, working in London and Sydney, she now freelances from an attic in Sheffield. As E L Young (in the UK, Emma in the USA), she is also the author of the STORM series of science-based thrillers for kids. This is an edited version of an article originally published by Mosaic, and is reproduced under a Creative Commons licence.

– Emma Young is an award-winning science and health journalist. A former reporter and editor on New Scientist, working in London and Sydney, she now freelances from an attic in Sheffield. As E L Young (in the UK, Emma in the USA), she is also the author of the STORM series of science-based thrillers for kids. This is an edited version of an article originally published by Mosaic, and is reproduced under a Creative Commons licence.

Learn more: